My WWII Service as a U.S. Army Paratrooper

As told to John Howsden

When the green light goes on, the jumpmaster slaps the first guy on the butt, signaling him to jump. The rest of us shuffle up as fast as we can, because once the first guy jumps, there can be no hesitation from the rest of the guys. You have to realize that the plane is flying 110 mph. Every second of hesitation puts you further off your drop zone, and into enemy territory.

— Joe Quintel

Early Life

I was born in October 1915, on a plantation in Waialua, Oahu. I was the third child of seven. My father was conscripted from Portugal in 1910 to work in the pineapple fields in Hawaii for five years. My whole family came over with Dad, and we lived there for 10 years. When we worked for the company, we were not paid money. Instead we bought supplies from the company store. They kept track of what we bought, and subtracted that from our earnings.

In 1920, when I was 5 years old, we moved to Oakland, California, and bought a house at 816 27th Ave. It was a two-story house, with 10 rooms. The boys slept upstairs and the girls slept downstairs. It had two bathrooms attached to the side of the house, but you had to go outside to get to the bathrooms.

While in Oakland, I went to Dr. Lazear Elementary, a school named after a doctor who had died of malaria while working on the Panama Canal. I next attended Garfield Junior High. Back then junior high went to the ninth grade. We were in the grips of the Depression, and money was tight. To support the family, I dropped out of school to work in the fields picking peaches, apricots, and tomatoes.

Things were going fine until 1948 when the State added an on-ramp to Highway 17. The state only needed seven feet of our property, but since the house was on the property line, the whole house had to go.

When I turned 10, in 1935, I went to work for the Boyle Manufacturing Company in Oakland. We made buckets, barrels, hoses and other gardening tools. I was a welder, getting 10 cents for every hundred buckets I welded, and I could weld a hundred per hour. Back then we didn’t have a machine shop. If the machine broke, you had to fix it yourself, and you didn’t get paid while the machine was down.

When the machines broke, a lot of guys would leave the building to have a cigarette. They had to go outside, because the superintendent didn’t smoke, nor did he allow any smoking in the building.

This rule was so strictly enforced that the foremen would patrol the bathrooms, checking for guys sitting on the toilet having a smoke. More than one person was fired on the spot for sneaking a smoke on the property.

I didn’t smoke, so I stayed on the line and fixed my machine. My boss took notice of my dedication, and in 1939, when the company created a millwright position, I was selected to fill it.

Fighting Fires

Although I was employed full time, in 1942 I became a volunteer fireman for the City of Alameda. In order to become a volunteer, we had to prove we could handle the fire hose. Two firemen took me and another new volunteer to the end of Park Avenue to see if we could handle the fire hose. They rolled out the hose, and started the engine.

The other new guy held onto the nozzle, while I held onto the hose a few feet behind him. The water pressure was so great that the hose tried to twist out of my hands, making it hard to hang on to. I was only five foot seven and 155 pounds.

We were barely holding on when the fireman running the engine said, “Let’s see if they can hold onto this.” He revved up the engine and the hose started bucking. A few seconds later it flew out of my hands. It didn’t take long before the hose ripped out of the other guy’s hands as well, and began flailing. The nozzle whipped around and hit the other guy in the chest so hard, it broke two of his ribs.

We passed the hose test, but I only stayed at the fire department for a month. They had us scrubbing the canvas hoses, polishing the equipment, and doing other work they didn’t want to do. I got tired of being used while they played cards or slept.

War Erupts

I was still working for Boyle Manufacturing when US Steel bought them out. I eventually ended up working there for exactly 43 years. I started January 7, 1935 and retired January 7, 1978. I had gone from being a millwright to a machinist, to retiring as a tool and die man.

While working at US Steel, the war erupted. Even though I had not been drafted yet, the war still affected us. I remember going to the movies and seeing news reels about the atrocities Japanese soldiers were committing in the South Pacific. These news reels influenced my opinion of the Japanese internment.

Personally I thought they were a good thing, and I’ll tell you why.

Seeing films of the atrocities the Japanese solders committed made me so mad that, when I stepped out of the theater, I looked up and down the sidewalk for any Japanese.

If I had seen any, I would have killed them on the spot.

If the Japanese had not been put into camps, there would have been mass murder.

Joining the Army National Guard

As a civilian I enjoyed shooting, and I wanted to do more of it, so in 1937 I joined the Army National Guard. I was a squad leader in a rifle company, and all we had were rifles. The closest thing we had to a machine gun was a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). They weighed over 15 pounds, and it seemed that the smallest guy in the company always got assigned that weapon.

For the National Guard, I took my basic training in San Luis Obispo. One of the things we learned right away was the cleaning and nomenclature of our rifle. At first we had WW1 Springfield rifles, a bolt action rifle with a five-round clip.

Then we got the new M-1 Garand semi-automatic rifle, with an eight-round clip. We learned to field-strip it, breaking it down into six parts for cleaning and oiling. All you needed was one live round to use as a tool. I practiced until I got so good, I could break the M-1 down in 15 seconds. I thought I was fast, but there was a kid who did it in 12 seconds!

At times, we would take the rifle into the shower with us. First we would wash the rifle with hot water, and then we would suds up and wash ourselves.

When we weren’t shooting or cleaning our weapons, we were marching. Some guys had two left feet and other guys had two right feet.

After basic, I did my weekend meetings at the armory in Alameda. Our two-week summer camps were done at San Luis Obispo or Chehalis, Washington.

Joining the guard paid off because I was able to shoot a lot, but I couldn’t shoot the .45 pistol very well. The shooting instructor made me grip the pistol with one hand, and I was used to using both hands for a steadier grip. But when it came to big bore shooting, such as the M-1 or the Springfield rifle, I was dead-on.

While in the Guard I was promoted to corporal. My hitch lasted three years, and I was starting another, when the order came down that all married men had to get out of the Guard.

I was married with one child at that time, so on November 14, 1940, I was honorably discharged from the Army National Guard.

They didn’t say why, but I suspect they knew we were headed for war.

Drafted

Although I ended up in the regular army when the war broke out, I didn’t join, they had to drag me in. In 1945, I was 30 years old and still living in Oakland with my family when I got my draft notice.

It read “Greetings from Uncle Sam. You are hereby ordered to the Army base in Oakland for your physical…”

Thirty guys showed up for the physical. The sergeant ordered us to sit in the chairs and take off our clothes. And I mean even our socks. We were told to follow certain colored lines, which took us to different stations where they checked us for hearing, sight, balance and some other very personal stuff. We had to cough, bend over and stand on one foot. At the end of the day, they told me I had passed, and they would be in touch.

True to their word, a letter arrived ordering me to Camp Beale Air Force Base, a few miles north of Marysville, California. I was still working at US Steel, so I walked into my boss’s office and told him I was leaving for the Army. About that time, the superintendent walked in and said the company had just been awarded a contract for the Army, to build them a half-million buckets in 22-gauge steel.

This was a problem because the machines would have to be adjusted to make the buckets in 22-gauge, and I was the only one who knew how to adjust the machines.

The superintendent asked if I was willing to take on the job of making the adjustments and producing the buckets. I said, “Sure, but what about my draft notice?” He took my papers and made some phone calls.

The next thing I knew my orders were put on hold until further notified. I ended up getting a crew of 20 women and two guys that were 4-F, to make the buckets for the Army.

Every month the draft board called the company to see if I was finished with the job. It kept me out of the war for 10 months, and that was in 1944-’45 when the fighting was really bad, especially in Italy where the Germans were digging their heels in.

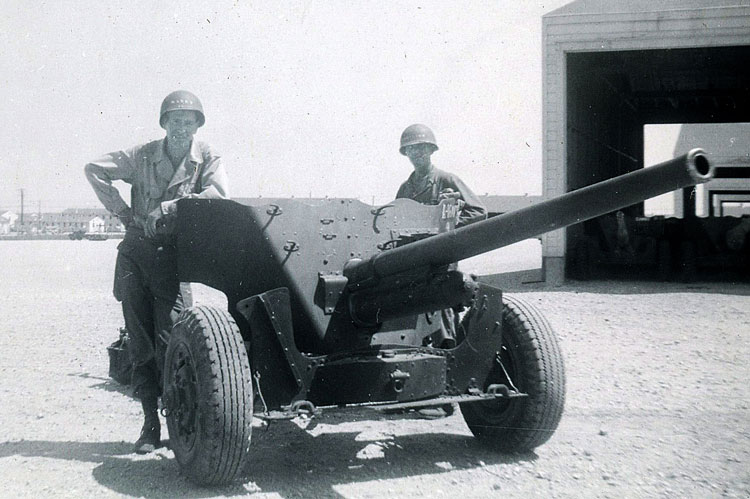

Joe (seated at center) at barracks at Camp Hood, Texas, 1944

Basic Training

Finally the job for the buckets was completed, and I went into the Army. I checked in at Camp Beale, where they gave me shots, a haircut and fatigues. When it comes to processing paperwork however, the Army likes all its boxes filled. When I joined the army, I did not have a middle name. The army said I needed one, so I pulled one out of thin air, and that is how I ended up with Ralph as my middle name.

When it came to the box asking me what I did as civilian, I told them I was a millwright. The Army figured no one would know what that was, so when I told him I had gone to night school to work on diesels, they listed me as a mechanic. I also fudged a little on the box about my level of education. I put down that I had two and a half years of high school. The recruiter told me the Army would “treat me better” if I had more education.

Once I had all the boxes on all the forms completed, I boarded a train for Camp Hood, Texas. The trip lasted five days and it was horrible. There were no sleeping cars, so we did everything sitting up, including eating, sleeping, and playing cards. All this without the benefit of showers.

Camp Hood, now called Fort Hood, is where I spent my six weeks of basic. Back then it was divided between North Camp and South Camp. South Camp was for basic training and North Camp was for the tank destroyer unit.

I was homesick for the first week, but they kept you so busy and tired that I forgot about home. They taught us how to shoot, salute and make our beds. After we learned how to march, we went on 20-mile hikes with our packs filled with 10 pounds of gear.

‘A matter of respect’

The food in basic was fair. When you looked at the menu at the start of the chow line, it sounded good. But how some of the guys served the food sucked. Some of these guys were P.O.’d that they were in the army, and they took it out on us. Instead of putting each serving of food in its proper place on your tray, they would just plop it down on top of each other. But you did not argue with these guys. If you complained, the service got worse, or you got assigned to KP (kitchen patrol).

However, later, when I got into the paratroopers, the food was excellent. On holidays we were served at the tables for 10 guys, and there were no “short stops”. What I mean by short stops is this: Say a platter with ten steaks was passed around the table. If you wanted a steak, you took one. Not everyone took a steak, so if one was left over when the platter reached the end of the table, you could speak up and have the platter passed back to you. No one could stop the platter on the way to you and take that steak. If they did, you could report them to your sergeant, and the next day that guy would be on KP. It was a matter of respect.

Being a paratrooper taught you respect and consideration for other people. Just like there was no cutting in the chow line. Anyone cutting into the line had to drop for 25 push ups and was assigned to KP the next day. The same went for running to the chow line. In the airborne, you ran wherever you went except when going to chow. Anyone caught running to the chow line got 25 push ups.

I was 30 years old when I went into basic. However, I was in pretty good shape. I had been playing baseball since grammar school, and was playing semi-pro ball when I went into the army. As it turned out, playing baseball kept me off of KP and guard duty. The major in charge of our unit put a baseball team together. When they found out I played semi-pro, they put me on the team as a catcher. Because I had baseball practice, I didn’t get any extra duty.

I could hit with either my left or right hand. I had a .280 average, and that’s the key to being on a baseball team, you have to have a “good bat.” If you can hit, they will find a place for you. Playing baseball kept my legs in good shape, which came in handy later when I went to jump school.

I had been in basic for only a couple of weeks when they posted a circular on the barracks door, advising that anyone wishing to become an officer should submit their application. Although I had only gone to 9th grade, I felt I was smart enough to be an officer.

I sent in my application, and one day, I was called before a sergeant for an interview. As I stood before his desk, he reviewed my application. He got to the part where I only had a ninth-grade education. He looked up from my application and said, “I have only one word for you — forget it.”

When I asked him what he meant, he said, “You aren’t smart enough.” This made me mad. I pointed to an officer on the far side of the office and said, “See that big guy over there? He is an officer with a year of college, and he is as dumb as a rock.” The sergeant chuckled, handed back my application and that was the end of my career as an officer.

Joe (at right) next to 57mm anti-tank gun

Anti-Tank Unit

After basic, I was assigned to the anti-tank unit. We pulled a 57mm (two inch) anti-tank gun behind what would now be considered a Humvee. We could set up the gun, fire it and hit the target in 15 seconds. We would shoot for the turret, hoping to jam it. The only problem was, the tank could still turn on its tracks and shoot back at us.

Since I was listed as a diesel mechanic on my enlistment papers, I also did the maintenance on the tank. But all this was going to change shortly. I got word I was being reassigned to the tank destroyer outfit on the other side of the camp. I didn’t want any part of that.

Tank destroyers, like tanks, are hot in the summer and sitting ducks in combat. I had talked to guys that had already seen combat. They told me how the Germans had cannons on their tanks, called eighty eights (88mm), that shot armor-piercing shells.

The armor-piercing shell is two shells in one. The outside shell hits the side of the tank first, heating up the metal and making it soft. Then the inside shell penetrates the soft metal and blows up inside the tank, incinerating everything inside.

A Movie and More

Having had my application for officer school rejected, and being stuck in the anti-tank unit, I was feeling pretty low. I went to the movies one Saturday to cheer up. They played a movie and then, as they normally did, ran a short clip of Japanese atrocities.

They finished up with an all-woman band that was pretty good.

Once the entertainment was over, two paratroopers got on the stage. With their pants bloused, boots shining and medals sparkling, they told us how great it was to be an Airborne trooper.

At the end of their presentation, they told us to meet them in the foyer if we were interested. I knew this was my ticket out of the anti-tank unit. They had their table set up in the foyer, with their pamphlet and application. I grabbed an application and filled it out.

When I told my master sergeant I was joining the Airborne, he said, “No, you’re not. You’re one of our best diesel mechanics, and I am not letting you go.”

I went back to the airborne recruiters and told him what my sergeant had said. They said, “Don’t worry about it. We’ll take care of it.”

Two days later the master sergeant called me into his office and said, “You have been accepted into the Airborne Paratroopers, but you’ll be back in a month.” On the way out, the Captain said, “You’re too old. You’ll never make it.”

I was old, but I was also determined. Once I got my orders for Airborne, I was shipped to Fort Benning, Georgia.

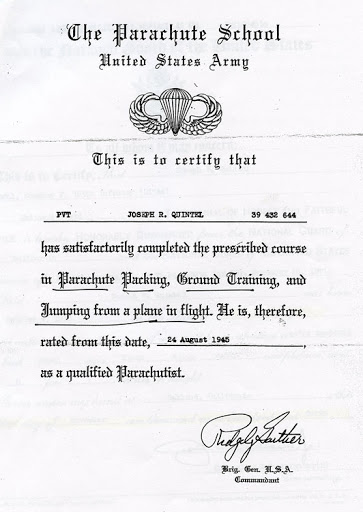

Parachute school, 1945, Fort Benning, Georgia

Paratrooper Training

Airborne wanted men with “stamina, determination and a little bit upstairs.”

There were four stages to the training; A, B, C and D, and each stage lasted five days. Stage A was rope climbing, judo, calisthenics, double timing, Indian clubs and stall bars. And if that was not enough, anytime we got into trouble, we had to do 25 push-ups.

We averaged 200 push-ups a day.

Rope climbing is tough and eliminated a lot of guys, but I had a strong grip from playing baseball. I used to practice gripping the bat as hard as I could. When I wasn’t practicing holding a bat, I was squeezing a tennis ball. Hanging onto a rope was not a problem. We climbed 15 feet up, rang the bell and climbed back down. Some guys had to use their feet, but not me.

Airborne wanted the cream of the crop, and Stage A was all about eliminating the weak. The sergeant’s job was to break us both physically and mentally, and they took their job seriously. They were so hard on us we called them animals. Not to their face, of course. We started on Monday with 120 guys, and by Friday we were down to 80 men.

We did not have tennis shoes. We ran in leather combat boots, fatigues and hats. We could not take off our shirts, even though it was in the 70’s with high humidity. Not only did we have to wear our shirts, we had to keep them tucked into our pants.

One time they put us in a sawdust pit to do push-ups. After doing our push-ups, we got up and stood at attention. They inspected for sawdust shavings. If you had one shaving on our shirt, you got a black mark against you, or what we called a gig; two gigs and you were kicked out of the program and sent back to your old unit. To avoid getting sawdust on our shirts, we did push-ups on our fingertips.

I was in basic in the middle of July. I sweated so much that by lunchtime, my fatigues were white from salt. At lunchtime I would stagger to the showers, stand under the water fully dressed and let the water wash over me until I was soaked to the bone.

Then I would drag myself over to our billet, which was nothing more than a slab of concrete with wooden sides and a canvas top, where I’d stretch out on the floor — don’t even think about lying on the cot — and wait until I was dry enough to go eat chow.

In Stage B, we started getting off the ground, but not into airplanes yet. We did tumbling, landing training, mock up doors, tower mock up, parachute packing and trainasium. A trainasium is a three-story scaffolding-type structure that you climb around to get used to heights.

Next we progressed to Stage C, which involved the control tower, tree tower, mock up doors, shock harness, more tumbling, and the wind machine. All this was designed to get us familiar with our equipment and heights.

For those who made it all the way to Stage D, this was the final test. Compared to the other three stages, physically this was the easiest. All you had to do was pack your chute, and do what fear and common sense told you not to do: Jump out of a perfectly good airplane flying 110 miles per hour at 1,500 feet.

Ready for my first jump from a C-46

First Jump

When the day came for our first jump, we loaded up in a C-46 plane. We had 12 guys sitting on each side of the plane, for a total of 24. At the front of the cabin were three lights: red, yellow, and green. When the red light went out and the yellow light came on, the jumpmaster, who was standing next to the door, yelled “Stand up, hook up, and check equipment!”

The order to check equipment meant to check the static line of the guy in front of you. The static line is hooked to a cable inside the airplane, and deploys your chute a few seconds after you leave the plane. You check the man in front of you to make sure his static line is over his shoulder and not under his arm. Jumping with the static line under your arm may cause you to dislocate your shoulder.

That is just one of the many things that can go wrong parachuting from a plane. For example, if you jump out facing the front of the plane, you’ll get knocked silly by a 110 mph blast of wind, plus the prop wash. I’ve seen guys who had jumped facing the wrong way do a somersault into the lines of their parachute. Next thing they know, they are plummeting to the ground at 13 feet per second, hanging upside down, with their parachute lines tangled in their boot buckles. If they don’t get to their knife in time to cut themselves loose, they are going to get hurt or killed.

We all carried our paratrooper-issue knives strapped to the outside of our calves. It had an eight-inch blade sharpened on both sides, much like a dagger. If you kept cool, pulled your knife, cut the lines, and righted yourself, you would land safely. Even so, I put tape over my shoe buckles as a precaution.

Even if you left the plane correctly and didn’t get tangled in your lines, you still had to make sure you were in a good vertical position when the chute popped open. The funny thing about parachuting is you have no sense of falling. But you had better be vertical when the chute opens, or you’re going to be whipped around with a sudden jolt.

Not only did you have to be straight up and down, you needed to have your chin tucked into your chest when the chute opened, or else the risers — the webbing connecting the lines to your harness — would smack you on the back of the head. They hit so hard that they dented our helmets.

Parachute training graduation certificate

Survival Skills

Of all the things that could go wrong, I only saw one paratrooper almost get killed. I was gathering my chute after landing, when I looked up and saw a streamer. A streamer is a parachute that comes out, but it doesn’t open. It just trails behind the trooper as he falls to the ground.

I figured this guy was a goner, but about 200 feet before he hit the ground, the chute opened. Still, I thought it wasn’t enough time to slow him down. He landed behind some trees, so I lost sight of him, but I heard him. He was yelling, “Help me, help me!” So I ran over there. He was all right, but his ankles hurt so much, he could not walk.

When the green light goes on, the jumpmaster slaps the first guy on the butt, signaling him to jump. The rest of us shuffle up as fast as we can, because once the first guy jumps, there can be no hesitation from the rest of the guys. You have to realize that the plane is flying 110 mph. Every second of hesitation puts you further off your drop zone, and into enemy territory.

Accidently landing behind enemy lines all alone was why the training was so rigorous and the selection process so grueling. The Airborne needed strong individuals who can survive and operate on their own. The second you jump out of a plane, you are on your own. Once you land, normally you hook up with your leader. However, if you land someplace other than where your leader is, you are going to have to function with your own wits and abilities.

If you did freeze at the door, the jump master braced himself, put his boots into the small of your back and kicked you out of the airplane. Some of the guys relied on the jumpmaster doing just that. Fortunately I never froze.

Night Jump

Later we started jumping at 1,200 feet, which takes 13 seconds to reach ground. At 900 feet it takes 8 seconds. I used to time each jump with the Waltham watch the army issued to me. Less time in the air is less time for them to shoot at you.

We only did one night jump. They did not say where we were going. We were only in the plane for 10 minutes when the green light came on, and we jumped. It was about eight o’clock at night. We landed in a peanut farm, which is where we normally landed. The government paid the farmer to let us use his field. We did not harm the peanuts, because they grow in the ground. Plus the sandy soil and leafy plants made for a soft landing, or as soft as it can be when you are falling out of the sky.

As time went on, we received special training and equipment. For example, if we landed in a tree and couldn’t get our regular parachute untangled, we were taught to release our emergency chute and let it hang down. Then we could slide down that parachute like it was a rope.

In addition to special training, we were also issued special rifles. At first we got a M1-A1 .30 caliber carbine, which was smaller and lighter than the M1 Garand carried by the infantry. When we were gearing up to invade Japan, we were issued an automatic carbine called the M1-A2. All you had to do was flip a switch, and it shot 850 to 900 rounds per minute.

The rifle came with two 30-round magazines curved like a banana, so we called them banana clips. We taped them together with the openings at opposite ends. When we emptied one magazine, we pulled it out, flipped it over and inserted the full magazine. We could shoot 60 rounds in less time than it takes to talk about it.

Although we had gone through a lot of training and had the best equipment, guys were still failing the program. On our fourth jump a guy by the name of Jim sat down next to me.

While we were waiting for everyone to get on board, the pilots were revving up the engines. For some reason I always got edgy waiting in the plane with all that noise and the vibration of the engines.

I looked over at Jim, and he was staring straight ahead with beads of sweating running down his face. I asked him if he felt okay. He didn’t look at me or say anything. He just got up, climbed out of the airplane and quit the program.

‘Show No Quarter’

Throughout our training the Army kept showing us films on the atrocities committed by the Japanese on our prisoners of war. First we saw films on the Bataan death march. The prisoners who were too weak to march were bayoneted to death. The films also showed Japanese soldiers bayoneting prisoners of war in China.

Other films showed prisoners being beaten, starved, or forced to stand in one position until their muscles gave out. One of the worst was seeing bamboo shoved under their fingernails and set on fire. Other times they pulled the fingernails off with pliers.

The Army wanted to “stimulate our minds so we would show no quarter.” When you met a Jap, you would want to destroy him.

We even got special training for the invasion of Japan. We learned not to trust Geisha girls, because they might carry hand grenades. Another trick we were warned about was the crooked picture. This actually was used in Germany. They would tilt a nice picture on the wall with a wire attached to the pin of a grenade. When someone straightened the picture, it would pull the pin on the grenade.

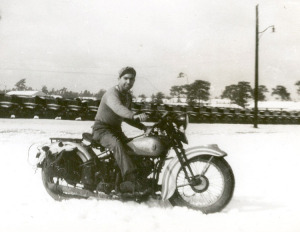

Joe astride his 61 cubic inch Harley-Davidson

Jumping with Explosives

When it came to jumping into Japan for the invasion, our primary goal was to blow up communication towers. We were assigned to carry explosive like C-2, primer cord and dynamite. I know it sounds strange parachuting out of a plane carrying dynamite, but it is safe.

During the Depression, I was around a lot of dynamite, working as a driller with the Civilian Conservation Corps. I watched as the delivery guys drove up in trucks, grabbed cases of dynamite and tossed them on the ground. It was safe as long as there is no detonator attached.

In order to blow up the communication towers, we had to find them. We studied pictures, aerial photographs, road maps and topographical maps. They even had an artist draw pictures of what the towers looked like at ground level.

On August 24, 1945, 20 days after they dropped the Atomic bomb on Japan, I graduated from the paratrooper school and was ready to invade Japan. I was assigned to the 82nd Airborne at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. We continued to train for the invasion. I jumped out of three different types of airplanes, the C-46, C-47 and the C119, or what we called the flying box car. I did 17 jumps in the Army and 14 after I got out.

When I wasn’t jumping out of airplanes, I worked in Ordnance. I worked on jeeps, tanks, trucks, you name it. I even maintained the military police motorcycles. They had Harley 45 flatheads. When it was slow, I worked on my personal 61 cubic inch Harley.

I was a full time mechanic, but I still had to jump once a month to qualify for jump pay. Being a paratrooper got you an extra fifty bucks month, a hundred if you were an officer.

Joe and cousin in 1949 at Oakland Estuary, next to 225 hydroplane topped with his trophies

Coming Home

I was still in Ordnance when the war ended, and I was elated to hear the news. I was discharged at Fort Bragg on July 27, 1946. A buddy and I hopped into his car and we headed for California.

We took the north route, stopping at Niagara Falls and Yellowstone Park. We wore our paratrooper uniforms proudly, just like the guys on the stage that Saturday at the movies. People knew we were with an elite group and treated us like kings.

Everywhere we stopped, people flocked around and thanked us. Sometimes they would pay for our gas and even pay for some of our meals. When they saw our jump wings, they asked us questions.

Matter of fact, I wear my original jump wings to this day. I have them on my belt buckle, and I am just as proud of them today as when I earned them 65 years ago.

Love and Marriage

I returned to my job at US Steel in 1946 and picked up where I left off. It was because of my job at US Steel that I met my second wife, Priscilla. A friend of mine that worked in the warehouse asked if I wanted to go on a blind date with him and his girlfriend.

I said sure, but his girlfriend fell and broke her arm, so I ended up going out with just Priscilla.

Priscilla had moved to California thinking all the houses had a lemon tree in the front yard and a red tiled roof. She had visions of people running around wearing shorts and halter tops.

I had just bought a brand new 1956 Royal Dodge Custom with a two-tone paint job, so we cruised around town looking at the houses and people. We dated for awhile and were married in 1958. We bought a house using the G.I. bill, and started a family.

In 1948 I quit playing semi-pro baseball. Later I took up racing 225 hydroplane boats. We traveled all over the state. One of the places we raced at was Lake Merritt in Oakland. On the straightaways you could reach 90 mph. It was a lot of fun, and I have a room full of trophies, but the best part was meeting all the nice people in the sport.

Joe and younger brother Manuel in front of a racing boat at the Oakland Estuary

Retiring to the Foothills

Although I had lived and worked in the Bay Area since I was 5 years old, our neighborhood in Oakland had changed. Three times, someone tried to break into our house. We were home at the time, so we could stop them, but our neighbors got broken into five times. The same year I retired, we moved up to Sonora.

Because of our age, we stayed out of the mountains. We did not want to be in the snow or have a house with a lot of steps. We bought our house before it was finished. The sheet rock had not even been taped yet. The yard did not have any trees. I had a lot to do. But I was retired and only 63 years old, so it gave me something to do.

I stayed in touch by letter with one paratrooper. Jim was a good guy until he started drinking, and then he wanted to fight everyone, including me. He lived in Wyoming. I never invited him out to California. I was afraid he would get to drinking and make a pest of himself. After a year I lost contact with him.

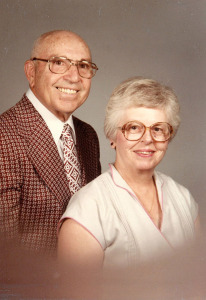

Joe and Priscilla in 1985

Reflections

I don’t dwell on the time I spent in the Army. I was an easygoing guy, and never had any problems to speak of. They had to draft me, though, because I knew I was going to get shot at. But we were at war, and it was something we all had to do.

I believe the military taught us discipline. When given an order, you learned to respect and follow the order. That is how I was bought up as a kid. My mom had a phobia about us kids getting in trouble with the law.

When I was growing up in Oakland, the police officers walked their beats. The call box for the officers in our neighborhood was at the end of our street, so we saw them all the time. They knew each one of us, and when they told us to go home, we did.

I believe the quality of one’s life is determined by respecting authority and making good decisions. We all have good and bad luck, but having a pattern of good decisions will make for a better life.

I am 98 years old and still blessed with good health. On September 13, 2013, my wife passed away, but we had 55 years together. In addition to all this, I have two wonderful daughters, Carol Quintel and Sharon Miller.

War is a terrible thing. You do what you have to do and then make the best of life.