Red Popke in 1944

As told to Chace Anderson

Red Popke in 1944

I’ve been Red Popke most of my life. Red because of my red hair and Popke because that was my dad’s last name. But I wasn’t Red Popke as a kid, I was Edgar Henning. And that’s a pretty interesting story.

You see, my mom was born in Germany, and her name was Maria Magdalena Henning. A lot of her story I learned only when she wrote it down shortly before she died.

Accompanied by two brothers and a sister-in-law, she came to this country as a young girl in 1911 and landed in Hoboken, New Jersey. In 1914, she married Adolf Ernst Popke, also an immigrant who had dropped the “Von” in front of his last name to make it sound less German. They separated often in a short, stormy marriage, but got together often enough that I have four brothers, three of them also sons of old Popke.

I hated my father. I never knew him but I hated him, hated the idea of him. I mean, how could a man leave a woman to fend for herself with all those kids? The oldest of the boys was Edward, then Ernest, then me, and then Elmer. My youngest brother, John, came along after Popke was out of the picture. No one in the family is quite sure how.

I was born in April 1923, in Jersey City, N.J., and I thought of myself as Ed Henning. It wasn’t until I was in high school and about to join my school’s branch of the Marine Reserves that I had to produce my birth certificate and saw for the first time that it said Edgar Popke.

No middle name, just Edgar Popke. And that’s interesting too, because all through the military and my adult life, my official papers say Edgar Henry Popke. I don’t know to this day where the hell the “Henry” came from.

Maria Magdalena Henning’s hand-written life story

A Boxcar for a Home

We were poor when I was a kid, but hell, everybody was poor. My mom kept us together, working odd jobs as a domestic in various places in New Jersey. When I was about seven or eight, her brother in Minnesota wrote and said he would help if she came out there. So she bought a second-hand Essex, never having driven a day in her life, piled us in and drove out to Minnesota.

We worked as help on a few ranches and truck farms, then found ourselves in Hollandale, Minn., working as sharecroppers and living in a boxcar. Edward, the oldest, was on his own, but Mom, Ernie, Elmer and I called that boxcar home for just about three years.

It was a wooden railroad car that had been taken off its wheels and moved to the farm. It had been a refrigerator car with two iceboxes on the back, and they became our closets. We had no water or electricity, and the outhouse was out back. We put up wires and hung blankets to make separate rooms. Mom slept in what we considered the kitchen. She cooked on a wood stove that also provided our heat, and the hanging blankets created a couple of bedrooms for my two brothers and me.

Red’s school picture from Hollandale, Minnesota

We grew onions and carrots … potatoes too. We had to weed the dirty bastards, and I was only big enough to weed two rows at a time. It was the early ‘30s, and we did everything by hand. I remember there was lots of snow in the winter, drifts almost as high as the roof. But the boards on the side of the rail car overlapped, and the woodstove kept us warm enough.

We had a path to the woodpile, a path to the outhouse, and a path to the rabbit pen. We ate veggies and rabbits, and raised a pig each year. I remember the hog’s head on top of a 50-gallon wood barrel we kept full of sauerkraut, and outside in the ground we piled carrots and potatoes in a big pit. We put straw and dirt on top to keep them from

freezing and then ate our way through the pit during the winter.

Of course we had to go to school, but it was about 4 ½ miles from the farm, and they’d make us stay there and sleep in the basement when the weather was really bad.

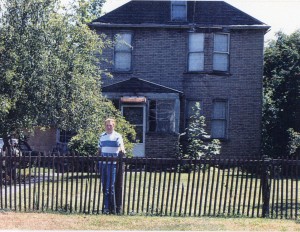

Red in front of his Mom’s home in Washington

Minnesota to Washington

Mom had a friend in Hollandale named Mrs. Carr who moved out to Anacortes, Wash. Mom kept in touch with her friend, and Mrs. Carr convinced my mother to move out there too.

Again we loaded into a car and started the cross-country trip. At night we’d go to a farm and beg some milk or extra food. I think we begged our way from Minnesota to Washington.

From Anacortes, Mom eventually moved us to Arlington, and then West Seattle. I went to West Seattle High School under the name Henning. In December of 1939, I was 16 and joined the Marine Reserve unit in my school. All we did was clean rifles.

First Service

In September of 1940, I was still in high school but was told if I volunteered for one year of military service, I wouldn’t be drafted. Now the U.S. wasn’t at war then, so I dropped out of school and joined the Army. Mom signed the papers because I was underage, and of course with me gone, there would be one less mouth to feed.

During the 13 months I was in the Army, I took enough classes to get my high school diploma and learned to drive just about anything with wheels. I spent most of the time at Fort Lewis, not far from Seattle driving a truck that pulled a cannon called a French 75.

I was only 18 when I returned from my Army duty. Some time earlier, I had put my name in at Bethlehem Steel in West Seattle, and shortly after moving in with my brother Edward, I answered the phone one morning. When the caller asked for Ed Henning, I said, “Just a minute,” and went to get my brother.

I forgot I had put in an application under that name. My brother ended up taking the call, went down to Bethlehem Steel, got the job and spent his entire career working for the company. Because it was a vital industry, he had to join the reserves but was exempt from active duty during the war.

I went to work chalking out steel plates at Todd Shipyard on the waterfront in Seattle. I’d lay out paper patterns on the steel plates, and then they would be cut and used for ships.

Uncle was a Nazi

Right when I got out of the Army, my mother received a letter from the German Red Cross saying that a brother who had stayed in that country had been killed when he was shot off his horse. Of course I knew Germany was already at war in Europe, but I didn’t know I had an uncle who was a Nazi.

Not only was he a Nazi, but it also turns out he was in the SS. One of my cousins went over to Germany right before we entered the war and brought back some of his medals. I took them around to show a few of my old buddies, and my cousin got mad at me for doing it. He wasn’t proud of the Nazi connection, so he threw all those medals in the Duwamish River in downtown Seattle.

Back in the Service

While working at the shipyard I got a notice from the Army saying I could go back to my old unit, or I’d most likely get drafted. So in about November of 1941, I got on a streetcar in Seattle and headed to the Navy recruiting office. As I walked up stairs, this old Navy Chief stuck his arm out and said,” Hey Red, where you going?” I told him I just got out of the Army and was thinking of joining the Navy.

“If you’ve already got experience, you’d be perfect for this new outfit,” he said. “It’s called the Seabees.” Well I signed up, and the Navy gave me a rating ahead of the other guys because of my time in the Army.

On paper, I was in the Navy when Pearl Harbor was bombed, but I hadn’t left Seattle yet. I don’t remember where I was when I heard the news. I do remember turning on a radio and hearing old Roosevelt declaring war.

1942 Norfolk, VA. Part of Company D. Red is in the back row, middle

Original Seabee

As the U.S. had moved closer to war, the Navy recognized a need for construction battalions and recruited skilled men for that service. Construction Battalion became CB, which became Seabee. I think the average age for Seabees early in the war was about 37, but I’ve read that some men were in their 50s and even a few in their 60s. Many of the original Seabees had helped build dams and highways across this country.

I was about the youngest of the lot, but had been given some responsibility because of my prior service. Here I was in Seattle, a skinny redheaded kid leading a bunch of older, grizzled recruits to the bus station to head for basic training in Norfolk, Virginia. I was a little full of myself marching them along. One of them, an older guy in his 30s named Jenkins … I guess he had had about enough of my bluster. He grabbed me by my shirt and held me up. I can still see him … missing front tooth … He said, “Popke, if we want any shit out of you, we’ll kick it out.” I think I grew up 15 years in 15 minutes that day.

It was about January of 1942 when we headed to Norfolk for basic training. I had never been to the south before and had never seen racial prejudice, didn’t know what it was – but I saw it in Virginia. In Norfolk we saw signs that said “No Niggers or Sailors Allowed.” I guess sailors there would get drunk and sleep it off on lawns.

I remember some of us were on a streetcar in Norfolk when some Negroes got on. They had a banjo and a guitar, so we asked them to play us some music. They said, “We got no place to sit, sir.” We gave them our seats, and right away the streetcar brake went on. The conductor came back and said to the blacks, “You people know better.” And then to us he said, “You people will learn. There’s the line.” There really was a line, and they had to sit in seats behind that line. We should have kicked the shit out of the conductor right there.

From Norfolk my unit went to Quonset Point, R.I. for more training, and then in May, we became the Third Naval Construction Battalion and were told to report to Port Hueneme, Calif. The first two construction battalions were called “Bobcats,” so we really were the first Seabees. I was assigned to Company D.

On June 20, we left Port Hueneme for San Francisco and then shipped out on the USS Cape Flattery on June 22. Lieutenant (jg) R.E. Flint was our commander, and let me tell you, old Flint was a good, good man. You ever have a problem, he’d say, “Let’s take this out behind the 20-holer and settle it there.”

Crossing the Pacific

The Cape Flattery was a Liberty Ship, one of those built in a hurry without much thought to comfort. They didn’t float very smoothly; made you feel like you wanted to jump right over the side. As soon as we went under the Golden Gate Bridge we started bouncing around, and most of the guys got seasick.

We were packed like animals among all the iron pipes down below, three hammocks to a section. When the weather got warmer, most of us slept up on deck.

Of course when we crossed the equator for the first time, all the old Navy guys felt they had to initiate us. I was an 18-year-old brat, a sneaky kid. When I saw they were blindfolding guys and making them walk a plank over a big portable pool, I said none of that for me. You don’t know where the end is, and I didn’t want any of that shit.

The older guys in the outfit understood nothing really bad was going to happen and just went along with the initiation pranks. But I figured a way to get out of the worst of it and ended up cleaning the cracks in the ship with a toothbrush as my initiation.

Landing in Fiji

I think we were about a month at sea before we landed in Fiji. After Pearl Harbor, the U.S. established its main advance naval base there. If the Japanese could seize the islands in the area, they could cut off Australia and New Zealand from America. But the Japanese defeat at Midway in June and the Japanese losses in the Solomons campaign changed things. Fiji gradually became a rear area used for staging and logistics.

Viti Levu and Vanua Levu are the two main islands in Fiji, and we landed at Suva on Viti Levu. I remember there was a group of native kids on the dock singing “You are My Sunshine.” Must have been the only song they knew because they sang it over and over again.

A coral reef surrounded the island, and there was an opening where you could bring a ship into the harbor. A Fijian in a canoe paddled out, met us and guided us in. He knew where the opening was.

Our ship was the first one in, but we had a sister ship behind us carrying all our equipment, everything from shovels to bulldozers and trucks. Apparently the captain of the second ship said, “No nigger’s going to run my boat,” and kicked the Fijian pilot off his ship. A lot of those guys were Merchant Marines rather than Navy men. Well, the captain tried to bring it in by himself and ran it aground on the coral. The ship sank right there, and Company D lost all its equipment.

They had a little airstrip in Suva, and we were there to enlarge it. But with no equipment there wasn’t a lot we could do for about three months, when we were resupplied from some of the other Seabee companies.

A guy named Pace was our metal man, and he figured out a way to mount a seat for me on this old frame and engine we found there. I was the driver for our company, so that little vehicle became our only equipment until supplies arrived. We just slept out in the open on mattresses we took from our ship. You could see the nose of the sister ship sticking up a little out of the clear blue water where it had sunk on the reef. They should have shot that captain.

There were Japanese civilians on Fiji, but no soldiers. The Fijians were strictly tribal and stuck to their own, but they were good to us. They were all about 5-foot-5 with fuzzy black hair. We called them “fuzz heads,” but not in a bad way.

I think they would have fought for anyone who showed them some kindness. I think the Fijians would have helped the Japanese soldiers if they had come there first and been good to them.

A petty officer and I might drive into a Fijian camp and tell the chief we need maybe 20 or 30 workers or something like that. He would babble something, and the next thing you’d know, 20 guys were ready to go. They’d work for us maybe a month. I never even knew if they got paid.

The Fijians helped us in so many ways. I think the Americans really screwed them up, though. Hey, one cigarette would buy you this and two cigarettes would buy you that. When the army came in, it blew their culture all to hell. They got spoiled. I think we ruined a bunch of them.

But I loved ‘em. To the Fijians I was colored … you know, with bright red hair. The women always wanted to change the color of their hair, and it wasn’t unusual for them to have it matted down with flour or whatever they’d use. Some would sneak up behind me and grab my hair and pull some out. See if they could match the color. Oh, I loved ‘em. I think I was respected by them too … got to have quite a following.

Red’s swimsuit made in Suva by a tailor working on the sidewalk. It was completed this in less than one hour with a hand-crank sewing machine.

If it had Wheels, I Could Drive It

Now keep in mind we were a construction unit; we were there to build things. If the outhouse got full, we could throw up a new 20-holer in nothing flat. And I could drive anything with four wheels, so most of the time I was hauling equipment, driving a semi all over the island.

On Viti Levu we worked on the airstrip, putting down metal matting over crushed coral and then driving over it with everything we had to pack things down. But the Japanese, they weren’t dumb. They’d fly over all the time, doing surveillance to see what we were building. Whenever we thought we had it just about completed, they’d have one of their guys come over and bomb a little bit of it. Because the matting was all interconnected, we’d have to start the whole thing over again.

After we finally finished the airstrip, my company went over the Vanua Levu, the other main island in Fiji. There we used jackhammers and dynamite to build tunnels where we could store 50-gallon barrels of gas. They’d be dumped overboard in nets from the supply ships and then float in on the tide. My job was to haul them from the shore to the caves.

Death in the Islands

Even though we were a construction unit, there was still death all around us. Old Tex, a great big guy and one of the good, good men in our unit, got blown up right in front of us. He was a lieutenant, and officers were the first off the ship whenever we landed. On one of our early liberties, he stepped on the dock to go ashore. As he was reaching over the rail he tripped a wire that had been set as a booby trap. Boom … that was the end … just like that.

We’d also see ships pass by with Japanese prisoners lined up on deck, just standing there wearing what looked like diapers.

Our destroyers would bring in American casualties, guys killed in combat somewhere in the South Pacific. We were told they couldn’t be buried at sea unless the ships were way out in certain zones, so the bodies were stored in the ships’ refrigerators, some dead quite a while and some that were still kind of limber. We had a special bugle call when a burial detail was needed, and I answered a few of those.

We wrapped the bodies and then would dig really fast to keep above the seeping water. Sometimes we’d stand on them to hold them down so we could get sand over the top deep enough to keep the dogs and stuff from getting at them. Just one body to a grave. We’d grab the dog tags and throw them in a coffee can. Didn’t mark the graves…I don’t know how anyone could remember where they were buried. As good as I knew that country, I couldn’t find them now. You get hardened to that shit and don’t even know it.

But that wasn’t the closest I ever came to death. I once went over a cliff in the jungle in my semi and would have been killed for sure if the rear wheels hadn’t hung up on the edge and kept the whole rig and me from going over. But there was another incident that could have been the end of old Popke.

On Vanua Levu we had a lot of equipment and stuff stolen, mostly, we figured, by the Japanese civilians on the island. At night we drew watch patrol and walked around the perimeter of the camp. Well, one night I’m out on patrol by myself, and I see some movement. It’s dark and I can’t tell who it is, so I give the command to identify. We had about 12 general orders, things you had to recite to identify yourself.

Well whoever it was came at me real fast with a knife, so I threw up my arms to grapple with him. In the process I took out my knife and stuck him, put my knife right through him. Killed him, I’m sure. He went down, and I’m thinking maybe there are others, so I hightail it back to camp to alert the base commander.

As I’m going back, I realize I’ve been cut, the inside of my right arm sliced open from armpit to elbow. Back at camp, Doc Howard, our Navy pharmacist, sat me down on a canvas chair and sewed me up like a sack of potatoes. No anesthesia…just some powder he threw in there. But the sew job stuck, at least until I got in a fight later on and busted it open.

As soon as Doc sewed me up I took a bunch of guys back to find the body, but there was no body to be found. There was blood all over the ground, but we never figured out how the body disappeared. The guys kidded me, you know …“Popke, are you sure you stabbed somebody?” The next day word was sent out to make sure no soldiers had turned up missing in the night. I have to assume I stuck a Jap civilian living on the island. I was just a kid, but I thought I was a man.

New Caledonia

We were about 14 months in Fiji. In August or September of 1943, my unit went over to New Caledonia. That’s where we first ran into some of those 90-Day Wonders…guys who went to college for about 90 days and came out officers. They didn’t know diddly shit, but were put in charge of a bunch of construction guys.

Over in New Caledonia we continued to blast and make more caves for storage, but we also installed a big degaussing station there. Every ship has a natural magnetic field that makes it susceptible to magnetic mines. Ships would come into our station to be degaussed – to have their magnetic field stripped so they wouldn’t attract those mines.

Driving Bull Halsey

My unit was in New Caledonia for about nine or 10 months, working on various projects, and to tell you the truth, meeting some interesting men. Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr. pretty much ran the show in the South Pacific, and held his Joint Chiefs of Staff meetings in Noumea, the capital of New Caledonia. Whenever he’d come, the base was on total lockdown … security reasons. He was the big shot. The enemy would have loved to get a piece of his butt.

Old Bull Halsey had his own driver, but that guy didn’t know how to get from A to B, so the admiral rode with me. One time when he came ashore, I was standing right next to him when he asked one of our commanders, “What are those guys over there doing?” He was told they were building an officers’ club.

“Where’s the enlisted men’s mess?” he asked.

“It hasn’t been completed yet, sir.”

“You get those men off that officers club and get them on the enlisted men’s mess,” he ordered. He wasn’t talking to me, but I heard him. Now some people will talk a lot of shit about Bull Halsey, but I’ll stick up for him. I drove him. He was a good, good guy.

The Family in1944: (L-R)

Back Row: Ernie, Mom, Edward

Front Row: Red, John, Elmer

The Trip Home

I remember our bugler, Charlie Lockhart, had a parrot from the islands that always sat on his shoulder; went everywhere Charlie went. And talk? Let me tell you, that parrot knew all the good words. Now Charlie chewed tobacco, and of course, some of the tobacco juice went through the bugle. That parrot would sit on Charlie’s shoulder and wipe juice off his face with its beak.

During the summer of 1944 my unit rotated home after two years at war. As we approached San Francisco, we got word that we couldn’t bring a parrot from the islands into the U.S. Doc ended up giving the parrot a shot. We wrapped him formally, added a lead weight, and then we had a funeral with the bird on a plank. The burial at sea ended up with Charlie’s parrot sliding over the side and all of us crying like babies.

As we pulled into the dock in San Francisco, I could see a woman operating a crane and another one driving a bus along the docks. That was unheard of when we went overseas. I guess things had changed.

Well, they wouldn’t let us off the boat. Old Man Flint told us they were sending us back out of the dock again. Apparently Eleanor Roosevelt had given some kind of order that servicemen returning from battle areas had to be re-sensitized to America, and our camp wasn’t ready yet. We all thought she was nuttier than hell. Found out later she was a smart lady. After two years away, we were pretty uncivilized. Death was nothing to a lot of guys, and many were pretty damn goofy.

The ship pulled out and we sat there in the Bay all night wondering what would happen next. I guess they figured it out because in the morning we pulled in again and were bused to Camp Parks out near Pleasanton. We found a chain wire fence around the whole place and were told there would be no liberty for a while. During that “re-sensitizing,” I got word somehow to my mother that I was back. So she and my cousin brought my car down from Seattle.

AWOL

I can’t remember how, but I got that car on base. After about a week, five of us looked at each other and said, “I think so.” We jumped in the car and headed to the gate.

A guard in spats and polish said, “Gentlemen, see your pass?”

We just said, “See ya.”

“Hey, you can’t do that.”

“The hell we can’t,” we said, and drove right out.

We had drawn two years back pay, so we headed to the Lake Merritt Hotel in Oakland and rented a bunch of rooms. It wasn’t hard to find ways to spend our money, but more than booze and women, we went after all the food we missed and saw a lot movies. I think a couple guys headed back earlier, but it was about a month before I took the other two back to the base with me.

Nothing really bad ever happened to us when we got back. Flint said, “You bastards, you. Red, you’re on Shore Patrol.” At the time I thought that was the worst thing that could happen to us – be military cops – but it worked out really good for me. I was on shore patrol out of Hayward and Castro Valley and spent a lot of my time around the hospital near San Leandro.

I was goofy after two years over there, but lots of guys were much worse. Lots of guys had terrible attitudes and no respect for anything. And many guys were in and out of the hospital there. If you mix alcohol and medicine in a goofy guy, you have your hands full.

I don’t think we were home a year when Old Flint came by and said, “Red, get your gear together, we’re going to Alaska.” I went to turn in my Shore Patrol gun, and the guy in charge of the whole thing outranked Flint. He said, “Red ain’t going’ nowhere. He’s frozen.” I guess I was too good at being on the Shore Patrol. I stood on the dock and waved goodbye to my buddies as they headed for Alaska. I took an apartment in San Leandro. I was still in the Navy, still in uniform, but I worked Shore Patrol with the San Leandro Police Department.

In August 1945, I was just going on duty one day when I saw this whole big band of guys coming down 14th Street in San Leandro. I thought, oh shit, we’re in for a good fight this time. I turned on the radio, heard the war was over, and realized those guys weren’t fighting, they were celebrating.

Civilian Life

About six months short of four years,

I got out of the service. It was Sept. 13, 1945, and they let me out early because I had compulsory reserve duty. For a bunch of years after that, I had to spend some time each summer training recruits in Port Hueneme.

For a while I just had a tough time being satisfied after the service. I lived with my brother in Seattle at first, driving a truck for this produce outfit. But after a year I said, “This ain’t getting me nowhere. I’m going back to California.”

There was work everywhere around San Leandro, so I took a job working assembly for General Motors, first in the car plant, and then I transferred to the truck plant. In the late 1940s I started taking some exams, you know, CHP, fire department, Railway Mail Service (RMS).

I decided to go with the RMS, but I also wanted the hell out of the city, so I bought the Haller Ranch out in Jacksonville. I had about 80 acres, just above what is now the waterline for Don Pedro, a town since inundated by Don Pedro Reservoir. My neighbor was an old guy we called Kanaka Pete. I remember Pete was fond of liquor and met the few visitors that came his way by pointing a rifle at them. He lived in a filthy little cabin on Kanaka Creek, and most of his belongings were scattered in and alongside the creek.

For my RMS runs I’d drive to the Bay Area, where we did the mail the way you used to see it done in the movies. There was the catcher on the side of the rail car that snagged a mailbag at 70 miles per hour. We’d sit in the mail car and sort the letter, put them into pigeonholes – there was one for every town on the run.

There were a bunch of really good guys in the RMS. The old-timers had been at it so long they could tell where they were by the beat of the track. Without looking up, they’d say, “So and so’s just around the bend,” or “We’re coming on to this or that town.” Just the beat of the track.

Pretty soon airmail started putting the RMS out of business, so I resigned about the time the new Safeway opened across from Hales and Symons in Sonora. I applied and started at the bottom … carry out, then dairy case, then produce. I sold the Haller Ranch and moved to an apartment on Stewart Street and then took a room in the house on Washington where the Radiator Doctor is now. From there I could walk to Safeway. Which is where I met Leona Sardella.

Leona was a checker at Safeway and of course came from a big Sonora family. I remember Mrs. Sardella with her accent always telling me, “Eddie, keep away from the Sicilians … Italians from the boot are no good. Stay away from the boot.” If any of her kids needed money, she kept a big roll inside her shirt. She would reach in and peel off what they needed.

Leona came from a family with lots of brothers and sisters. Curly was born in the old country and was strong as an ox, with arms like iron. Everybody knew Miller and Reno and Johnny, but Miller especially because he was the sheriff for so long.

In the 50s Safeway transferred me to Everett, Wash. Leona and I were madly in love … couldn’t do without each other. So I moved her up there with me, we got married, and in 1958, our daughter Tina was born.

I started getting promotions. At first it was assistant manager, and then I became manager of a store in Snohomish, about an hour from where we lived. It seemed like I was away from home all the time, working late at the store or driving back and forth. Pretty soon we were fighting over every little thing and eventually decided to call it quits, get divorced. Her brother Johnny came up and took Tina and Leona back to Sonora.

Of course I had to see my daughter, so I would make the odd trip down to Sonora. One thing led to another, and after a little while I asked for a transfer back to Sacramento because Leona and I were seeing each other again. And then we got married a second time, in Reno I think. Just the two of us and a justice of the peace.

I was still working in Sacramento, but Leona didn’t want to leave Sonora again. So I ended up quitting Safeway, and I went to work for Foster Brothers Market on Stockton Street, down where Bertelli’s is today.

Now this was the late 50s, maybe 1960. I know my twin boys were born in 1960. I named them Ed and Ed; well, Edward and Edgar, but I never had any problem calling them Ed and Ed. They always knew who I was talking to by the sound of my voice.

The Sheriff

Miller Sardella at that time owned a small cabin on Sullivan Creek, and that’s where we lived. I had a little Ford, but not much else. Leona didn’t even have a washing machine. But we were madly in love and all that bullshit. Things were good.

Pretty soon I found out Foster Brothers was going to sell out to a grocery chain, so I applied at the Sonora post office, and with my RMS experience, I got on there. To make the job full time, I did the janitor work and everything else.

We moved our family to a house where Reno Sardella used to live, and then Miller bought a ranch out on Wards Ferry Road. He asked us to move out there and run the ranch with him … run cattle and all. So that’s what we did.

Through the 1960s I worked full time at the post office and just about full time at the ranch; up at 4 a.m. to put out sprinklers, then into town. Leona eventually went back to being a checker, and started working at Save Mart. And I worked my way up to assistant postmaster.

I’ve loved horses all my life, and at the ranch I got to work with them just about every day. I remember Ed Bigelow, the local Ag Commissioner, used to come in for his mail and one day talked me into joining the Sheriff’s Posse. I was a member all through the 1960s and served as captain in 1965. At the same time I was on the Tuolumne County Fair Board, and I think that’s when I joined the Masonic Lodge; I’m still a Mason to this day. I guess you could say I was pretty involved in this area.

Miller came to be my best friend. We were like brothers. We busted horses together, branded … whatever needed to be done. Even shed a few tears together. He was a little fella, but he had balls; I’d back him any time. And he was a good sheriff; everybody liked Miller Sardella. I never saw him drunk or cheating, but I sure saw him do a lot of good as sheriff.

I told you about old Kanaka Pete out in Jacksonville. Well it came to pass one time that Miller had to arrest Pete for one thing or another, but he knew Pete tried to shoot anyone who came close to his place. So Miller waits until Pete is in town having a drink at the Sportsman. While Pete is talking to Vic Filiberti, the owner, behind the bar, Miller quietly goes up behind him, grabs his wrists and slips the cuffs on him.

And Miller liked a joke as much as the next guy. I remember the time he goes into the Sportsman and says to Vic Filiberti, “You ugly Italian wop, you dago so and so. I’m tired of you bad-mouthing me, and I’m tired of all these rumors you’re spreading about me and all this bullshit and it’s time to put an end to it.”

Filiberti says, “Yeah, yeah, and what are you going to do about it?”

Miller says, “I think I’m going to kill you.” He pulls out his gun—he had put a bunch of blanks in it—and shoots Vic. Well Filiberti turns white, and then slowly he realizes he’s not dead. Meanwhile Miller runs down to the Sonora Inn and hides in a room because he knows Vic will spend all day looking for him. I was there. I saw it. Oh, there were so many good guys up and down the street in Sonora back then. And so many stories.

I kind of figured we’d eventually build a house of our own on Miller’s ranch, but it didn’t work out. As his son took more control, I knew it was time to move on. My boys were getting older, and it was about then their teachers at school decided they had to call one of them John so they wouldn’t be confused by Ed and Ed.

Around 1974, I moved the family into a home we bought in Jamestown, and then I started looking for a job as postmaster. I put in for one in Riverbank and got it. It was no fun to commute, so we sold the house and moved to Modesto. We were there maybe a year, and all of a sudden Leona was unhappy. She ended up going back to Sonora. Ed went with her, John stayed with me, and by then Tina was on her own in Manteca.

We divorced as the boys were finishing high school, so it must have been 1978 or ’79. Leona and I went our separate ways.

Carolyn and Red in 2012

From Place to Place

In September of 1981, I married my Carolyn, my present wife, and four months later I retired from the post office. Since then I’ve worked at things like selling cars, doing security work, and helping with senior services.

Now Carolyn doesn’t mind moving, and that’s what we’ve done the last 30 years. When our Sonora house burned in 1983, we lost just about everything, including photos from the war and many of my documents. But that fire and my mother’s death gave us a reason to move up to Pe Ell, Washington. After five years in Washington, we moved to Grants Pass, Ore., and then to McGrath, Minn. From there we moved to Lake Pomme de Terre in Missouri, then back to Modesto, back to Sonora, and back once more to Washington.

In June of 2011, I had a little stroke and spent three weeks in the hospital. No paralysis, but it does affect my memory a little. Did you notice? After that we wanted to be a little closer to my boys, so just over a year ago, we came back to Sonora. And I think I’m staying this time.

Reunions

Twice since I married Carolyn, we’ve gone to reunions of the Third Construction Battalion, once in St. Louis and once in New Orleans. I saw many of the guys from the South Pacific, and Old Flint even came to one of them. He was up there in age, but even then he looked like he could take someone out behind a 20-holer to settle a beef.

On the reunion trip to St. Louis, Carolyn and I went through Hollandale, Minn. to see if we could find the farm where I lived in that railroad car. We came upon a spot that looked familiar, a place we used to flood for an ice rink in the winter. I stopped to ask a neighbor across the street about the boxcar, but he said he hadn’t lived there long enough to know. He pointed me to another house, saying the family in it had been around a long time.

When the next guy answered the door, he said, “How’s the postmaster from Sonora?”

I said “What the hell?” He then told me that years earlier he had visited his mother in Sonora and had gone to the post office to mail a post card. Apparently I was working the window that day, and when I saw the card was addressed to Hollandale, I mentioned I had lived there as a kid.

He then pointed down the road and said, “Yeah, your boxcar was right over there among all the coal cinders.” He added, “And I do remember a little red-headed kid who used to live there.”

Red’s VFW hat and some of his medals

No Regrets

I look back on my life, and I have no regrets. I think the best time was when my kids came along. But the service was good too. Not only for lessons I learned, but also for the men I met. I knew a lot of guys who would put their life on the line for you.

Whatever success I’ve had in my life is due in large part to my time in the service. That’s where I grew up. I was just a kid when I went in. There had been no father in my house. A lot of older men in the Seabees gave me advice, taught me how to act. And that did a lot to make me a man.

Red Popke in 2012

Transmittal of and/or Entitlement to Awards

Edgar Henry Popke

Good Conduct Medal (Navy) (USMC)

World War II Victory Medal

Naval Reserve Meritorious Service Medal

Navy Occupation Service Medal

Organized Marine Corps Reserve Medal

Reserve Medal, Armed Forces (Navy)

American Defense Service Medal

Meritorious Unit Commendation Ribbon

American Campaign Medal

Marine Corps Reserve Ribbon

Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal