My Service as a WWII Navy Radio Technician

As told to Mary Louis

Seaman 1st Class Bob Allured

Seaman 1st Class Bob Allured

It was while I was in New York, that President Roosevelt died. I was at a canteen when some other servicemen and I saw the headlines in the paper. From the photo in the newspaper, I can see that I was just as upset as the other guys – even the English sailor displayed concern. We wondered how Roosevelt’s passing would affect the war. — Bob Allured

My Early Years of Struggle

My early life sounds like an old West, Depression-era story. It begins with my parents, William Henry Allured and Sara-Margaret Reynolds, marrying and moving to Cima, California, which was just across the border from Searchlight, Nevada.

Dad was a miner in a dry camp there, with his father and brother. Mom became pregnant for the first time but miscarried due to the hardships of living with no water around.

When she became pregnant with me, she insisted that they move to civilization. So my father moved them to Los Angeles, where his parents had their permanent home. I was born Robert Taber Allured in May 1926 in Los Angeles.

My next younger brother, Richard Reynolds Allured, was born in Long Beach, where Dad was an undertaker. Dad became unhappy with the undertaking business, so he moved us up to Jackson, Amador County in 1928, when I was two years old. My youngest brother, Walter Scott Allured, was born there.

Dad went back to the line of work that he knew best and loved – gold mining. He worked at another dry mine three miles outside of Jackson. We had to carry cans of water out to him. Mom pretty much supported the family on her $1 a day wages as a nurse.

Apparently my dad didn’t find enough gold to contribute to the family’s sustenance. We ate just two meals a day, breakfast and supper. Both meals consisted of oatmeal.

I remember my mother telling Dad that there was no milk, so he would pick up a bucket and later return with it filled with warm milk. He milked the neighbor’s cow by backing it up against a tree, or their fence, so he could milk it.

My parents argued over finances and divorced in 1934, when I was eight years old. My dad left and joined the Army Transport Service as a civilian, on a “Navy-looking” ship at Fort Mason in San Francisco.

Mom moved us to Mountain View, in the South Bay, where her mother lived. Mom had to look for work. In order to work full time, she farmed us kids out to people she knew and paid them for taking care of us.

Mom still worked as a nurse there in 1934. Of course, just about everyone in America was barely scraping by, due to the Great Depression.

I went to Los Altos Elementary School, which was near Mountain View. I had just started high school there when Mom received a job offer back in Jackson. She asked us boys if we wanted to move back to Jackson, and we all voted “Yes!” So she moved us back “home.” I attended Jackson Union High School for a couple of years, but grew restless and ran away.

I went to the Stockton Post Office and tried to enlist in the Marines at the age of 15.

They sent me home. In high school, I played football and hooky a lot. I drove a dump truck when I wasn’t in school.

Finally, when I was 17 ½ years old, Mom signed for me to enlist. She had an agreement with the principal of the high school that if I enlisted early, with only half a year of school left, he would let me graduate. I had to wait until football season was over so our team would have enough boys to play. So that’s what I did.

On Nov. 29, 1943, I went to the Stockton Post Office with two of my friends, Ernie Gianini and Bernard Chulich, who were already 18. I enlisted in the Navy because it was the only service enlisting people under 18.

Bob (back middle) with friends

Bob (back middle) with friends

Basic Training

I was sent to Faragut, Idaho on December 1, 1943, for six months of basic training. Once, while I was marching in review, I passed out and was diagnosed with “cat fever,” or mumps. I was confined to a hospital in isolation for the duration of my illness.

I qualified as a marksman on both indoor and outdoor ranges. I passed the swimming test, and also became a night lookout trainer, receiving gas mask gas chamber instructions.

On May 6, 1944, I reported for duty at the Radio School there in Idaho for 10 weeks.

I became a radio technician, learning to repair communication radios and high frequency sonar.

In June 1944, I took a two-day liberty and went home to Jackson and graduated. I didn’t tell my mother or brothers ahead of time. I just walked onstage at the end of the line and received my diploma, to their amazement. They were in the audience and saw me graduate.

On Aug. 10, 1944, I was assigned to the boat basin at Oceanside, California at Camp Pendleton Marine Base. My habit of playing hooky followed me there. One time I didn’t report back to base at night.

When I showed up in the morning the base commander, Art Adams, assigned me to garbage detail. Interestingly enough, Art became my boss at PG&E in San Mateo later in my civilian life.

USS Gridley

USS Gridley

Deployment aboard U.S.S. Gridley DD380

On Aug. 13, 1944, I shipped out on a troop transport from San Diego to Pearl Harbor. It was still a mess from the Japanese bombing in ’41. In September 1944, I was deployed on a destroyer, the U.S.S. Gridley, DD380.

The Gridley was in destroyer division 11, squadron 6. Its motto was “Fire When Ready.” A nickname for the Gridley was “The Grey Ghost of the South China Coast.” Our role was to patrol and escort battleships, and provide screening for aircraft carriers. We also rescued downed American pilots.

Some of the highlights of our deployment were supporting the American landings on Peleliu in the Central Pacific on Sept. 15, 1944 and assisting aircraft carriers in battles near Okinawa, Formosa, and Aparri (Philippine Islands), and the Visaya (Philippine Islands) raid October 10-19, 1944. This is according to my Navy personnel records. I remember that we were involved in quite a battle off Guam at one point. The Gridley and the DD McCall were involved all day in a firefight against the Japanese, firing on the deep part of the beach and also further inland.

At night we pulled our ships further out to sea to rest. But we kept seeing a light flashing on the beach. The McCall sent a boat to investigate the flicker of light and discovered Radioman First Class George Tweed. He had been stuck there since the beginning of the war. In October 1944, the operation in the Leyte Gulf of the Philippine Islands was heating up.

On Oct. 28, 1944 we sank a Japanese submarine, T-54. The days that followed were filled with fighting off the Kamikazes, which were often Japanese light bombers called “Bettys.” Several of our carriers took severe hits in the battle, and the Gridley escorted the damaged carriers (the Franklin and the Belleau Wood) to Ulithi, in the Caroline Islands of Micronesia, on Nov. 2, 1944. But two days later we were back in Leyte Gulf.

Captured Kamikaze Pilot

Once we shot down a Kamikaze, and there was a survivor from the fighter plane. I was asked to sit with the fellow until we could transport him in captivity to another carrier.

He didn’t speak a word but he kept moving his mouth in some “mysterious” way (at least it was unusual to me). When we turned him over to the prisoner carrier, it was discovered that he had been chewing his tongue in an attempt at committing suicide.

I thought that was pretty gruesome!

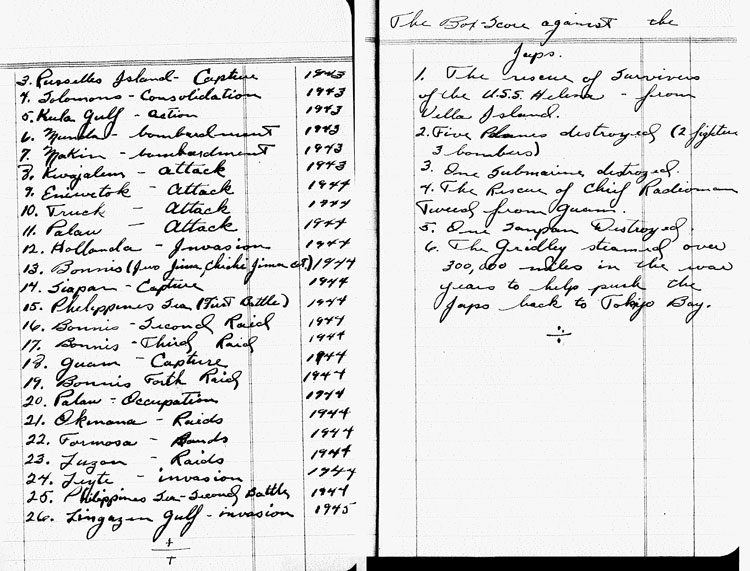

Pages from Bob’s journal kept while he was on the USS Gridley

Pages from Bob’s journal kept while he was on the USS Gridley

Deafness and Heroism

We continued to provide patrol and bombardment support for American landings in Lingayen Gulf, in the Philippines. Unfortunately, during our bombardment duties, I was walking under the 5-inch #1 gun on my way to my position on the #2 gun, when it went off. I lost partial hearing in both ears because of that. My personnel records state that we were involved in the Philippines battles from Oct. 20, 1944 through Jan. 20, 1945.

Towards the end of our duty in the Philippines the Gridley’s fan-tail was hit by a Japanese bomber. I was near the fan-tail with this young kid; somehow he got into the Navy at the age of 15. We had to shut the back hatch so that the seawater would not rush into the rest of the ship.

We struggled with the hatch until the kid finally said he would go into the seaward side of the hatch and push it shut. I told him to get out, but he wouldn’t. Together we succeeded in closing the hatch, but that kid died a hero – the Gridley was saved.

We went on to other action and kept that hatch closed. I received two stars and a Good Conduct Medal for participation in the Philippine Liberation. I also received four stars for battles in the South Pacific. I remember the Gridley went other places in the South Pacific while I was deployed on her. I saw the coast of Australia, but we never went ashore. It was when we went to the South Pacific, that I crossed the Equator for the first time. I went from being a “pollywog” to a “shellback.”

We were in so many places in the Pacific that I cannot remember when I was where. Fortunately I recorded the Gridley’s battles with brief notes in a journal while still aboard. That’s how I remembered the story about the rescue of George Tweed.

Toys for the Marianas

Somewhere in the mix of all those battles, we stopped at the Mariana Islands – I think it was sometime in late 1944.

I noticed the children had virtually no toys, so I wrote home and asked my mother to send some toys for those poor kids. But when the toys caught up with our ship we never returned to the Marianas. What Mom had sent were toy trucks.

Since we were not returning to the Marianas, I decided to have fun with the trucks myself. One day I took a couple of the trucks, which were pull toys, on deck. I started pulling one of the trucks around just as the ship’s doctor walked by.

I said, “I think I need a discharge.” His reply was to pick up the cord to the second truck and started pulling it around too. I could tell by his “response” that there would be no discharge for me!

Back to the Mainland

My final trip on the Gridley in the Pacific was to escort the battleship Mississippi to Pearl Harbor. Then we sailed to San Diego for preliminary repairs and through the Panama Canal to New York, arriving in the spring of 1945. The ship needed a lot of work because it had spent 28 months away from any major repair facility.

It was while I was in New York, that President Roosevelt died. I was at a canteen when some other servicemen and I saw the headlines in the paper. From the photo in the newspaper, I can see that I was just as upset as the other guys – even the English sailor displayed concern. We wondered how Roosevelt’s passing would affect the war.

Mediterranean Duty

On June 22, 1945, the Gridley was given a clean bill of health, so we left for the Mediterranean. We spent the next seven months providing passenger transport, shipping freight, and convoy operations, much like we did in the Pacific. It was kind of “R & R” duty for us.

Our first stop was in Casablanca. From there we went to Oran, Algeria, Naples, Italy, and Nice and Marseilles in France. Just outside of Nice was a favorite place for our commander called Villefranche-sur-Mer. Apparently he had a girlfriend there, so we returned quite a few times.

At Villefranche, I met a family who operated a little café near the beach. I was always stuck on guard duty aboard ship while just about everyone else had liberty in town.

Claire

Claire

So the owner always prepared me a nice sandwich and sent her older daughter to the ship to deliver it to me. The girl’s name was Claire.

From Villefranche, the Gridley took us to Marseilles and then back to Casablanca. We knew it was our last stop before going back to the States, so we partied pretty heavily.

I partied a little too much and missed the ship the next morning.

It wasn’t exactly like I played hooky again; I just did not report in a timely manner. I was housed with a bunch of soldiers who had been fighting Rommel in a tank squadron, I think in Patton’s Army. Boy, did they have stories to tell!

The next day or so a troop transport left for the United States. I think I was only one of two sailors on board with all those soldiers. We landed in Richmond, Virginia.

Submarine School

I received orders on Nov. 26, 1945 for sub training at New London, Connecticut, so when I arrived in Richmond I had to take a train north, through Washington, D.C., on to New London. I arrived there on Dec. 20, 1945.

My records state that I “completed a course of instruction in use of the Lung (a rebreathing device which allowed sailors to escape from sunken submarines), having made escapes in the Submarine Training Tank at depths up to and including 100 feet.”

This is how I describe the experience: Each of us trainees took turns at entering a chamber, which was then closed, and the pressure in the chamber was built up.

I had to climb a 100-foot rope to the surface without oxygen, while slowly blowing out my breath every five to ten feet. At the top, the “hatch” was opened.

There were trainers accompanying us on this climb, to make sure we did the technique correctly. The object was to train us to escape a submarine without getting the “bends.”

While there, I also passed examinations for radar and sonar training. The sub training lasted 14 weeks, until I officially could be called a submariner.

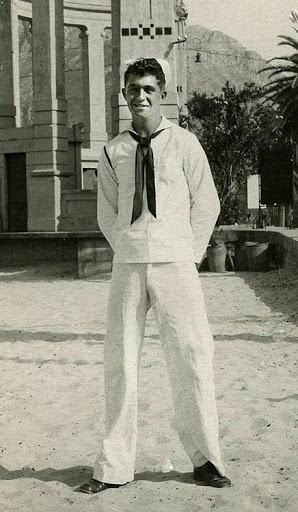

Bob in Palermo, Italy in 1945

Bob in Palermo, Italy in 1945

Decommissioning of the Gridley

While I was in sub school, I had to go to Brooklyn Navy yard; the reason escapes me now. While there, I saw an officer from the Gridley and he told me that our ship was being decommissioned that day. He invited me into the room for the ceremony. I was given a decommissioning pennant from the bow of the Gridley. I still have that pennant. It is a little worse for wear, having been a little moth-eaten.

I was taken to Key West, Florida in a sub, and from there I flew to Sacramento.

I hitchhiked home to Jackson. The first ride I had from Sacramento was from a sailor driving a big town car. He had received the Congressional Medal of Honor. He showed it to me. He dropped me off on Jackson Highway so I could hitch the rest of the way home.

After a brief leave, I hitchhiked to Treasure Island to report for duty. That was just a stop over en route back to Pearl Harbor.

Return to the Pacific aboard the Besugo

It was at Pearl that I reported aboard the submarine Besugo, SS-321, in May of 1946. The Besugo was a relatively new submarine, having been launched in February, 1944, and was unique in carrying two five-inch guns on its deck, one forward and one aft.

I was proud to be aboard the Besugo because the ship had a distinguished war record, having sunk a German sub, a Japanese oil tanker, a landing ship for tanks, a frigate and a minesweeper.

The Besugo had been freshly overhauled in San Diego in the fall of 1945 and had been operating out of Guam until its trip to Pearl Harbor on May 6, 1946, where I went aboard. I learned of its history when I went aboard from other seamen who had already been with the Besugo earlier.

USS Besugo

USS Besugo

The Besugo muster rosters showed I was on board in August 1946, October 1946, December 1946, and February 1947. I was actually aboard continuously during that time, except for a brief leave home sometime in 1946. But not all of the muster rosters were correctly recorded.

Meeting My Stepmother

While I was stationed at Pearl Harbor, I received word that my father would be in Honolulu. He was now a commander in the civilian Army Transport Service, which had been stationed in Australia. I met him there and he introduced me to my new stepmother. He had met this woman in Australia and married her.

She spoke with an Australian accent. Dad wanted to see “my” submarine so we went back to Pearl. When he walked aboard in his commander’s uniform, it caused quite a stir among my fellow servicemen, who were resting on deck in their T-shirts in the shade. They jumped up and saluted him.

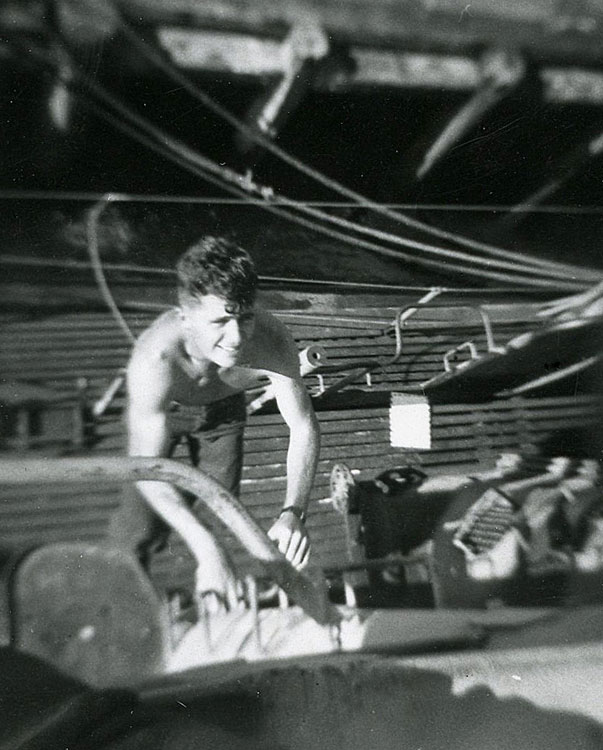

Bob climbing Besugo conning tower ladder

Bob climbing Besugo conning tower ladder

Life Aboard the Besugo

Unfortunately I cannot remember all the excursions I made aboard the Besugo but I do remember that we arrived at one of the Bikini Atolls in July 1946, because that is when they were testing atom bombs there.

We received orders to dive to the depth of 100 feet. We later learned that an atom bomb was being tested while we were in the waters nearby.

When the cloud had cleared we were told we could surface. I didn’t think of this at the time, but now I wonder if any of the atomic fallout was still in the air when we surfaced.

Bob (top left) helping crew of Besugo retrieve Japanese torpedo, circa 1946-’47

Bob (top left) helping crew of Besugo retrieve Japanese torpedo, circa 1946-’47

Another interesting episode aboard the Besugo was when we discovered a Japanese torpedo and took it aboard. I even have a picture of it. The war may have been over, but the clean-up was ongoing.

We had a small male dog aboard the Besugo that was named Sugie.

He was so used to submarine life that he was only used to men and only knew how to go through doorways the “submarine way” – the door thresholds on the submarine were too high for him to get his little legs over, so he would jump up onto someone’s shoulder. Then the person would walk through the doorway and Sugie would jump off.

I took Sugie home to Jackson once while on leave, and saw that he could not walk through a normal doorway either.

Sugie on the Besugo, sailor unknown

Sugie on the Besugo, sailor unknown

There are pictures of Sugie at the sub station in New London, Connecticut and he is on the internet too.

Discharge

I had to wait until age 21 to be discharged, because I joined the Navy before I was 18. In order to have credit for four years of service, I could not discharge until after my 21st birthday. On May 8, 1947, I received my official discharge papers at Yerba Buena, San Francisco. I then hitchhiked home to Jackson.

I was automatically enlisted in the Navy reserves for five years upon discharge, but I wasn’t called very often because there wasn’t much need for submariners after the war.

Back to Civilian Life

Once I was back home in Jackson, I worked at Sausman’s Garage for a year. Then I worked as a taxi-cab driver. The work was not steady enough, and the need for a “real” job became apparent to me in 1948.

I had met Betty Greve in June of 1947, one month after my discharge from the Navy. We met at a roller skating rink in Martel, which is close to Jackson.

We had begun courting seriously before 1948, so I knew I needed a good job to support a wife. I went to work for PG&E in 1948, at first as a temporary hire. The job became permanent within 6 months.

I think the reason I was hired was because PG&E figured out if I could handle the electronics and sonar aboard a sub, I could deal with ordinary electricity!

Betty and I were married on Jan. 5, 1949. Betty’s father “Shorty” Greve took me under his wing, as I had grown up without a father figure for much of my youth. He helped me grow up and become responsible.

After being hired by PG&E, I worked at powerhouses – Tiger Creek, Old Electra and New Electra, on the Mokelumne watersheds. I worked there for three years until I was transferred to the Oakland power control office.

The power control office was in Oakland because initially, there was no room for our staff in San Francisco.

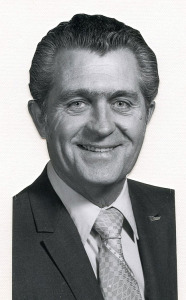

Bob during PG&E years

Bob during PG&E years

Eventually I was transferred to the San Francisco office.

Betty and I had three children. Our firstborn was our daughter, Yvonne Diane, born in June, 1950. The following year we had our first son, James Scott, and in 1956 our son Charles Robert was born.

I worked rotating shifts for PG&E so in order to support my family I also worked as a reserve deputy sheriff in Contra Costa county during my “off” hours from PG&E.

I eventually reached the rank of Captain in the sheriff’s reserves. In order to work this second job, I had to go through law enforcement training. This put a strain on the family – Betty was the only parent the children saw for quite a while.

I belonged to the American Power Dispatcher Organization. I was the National President for a while. There were several perks that came with that membership, for example, we were able to travel with them to many different places for their annual meetings. The ones in Hawaii were the most fun.

During my working career, after the children were grown, Betty and I took a memorable trip to Ireland, to visit some of Betty’s relatives.

We visited the home where her grandmother was born. It was a stone hut with a dirt floor, and they cooked over an open fire, using peat turf for fuel. While in Ireland I visited a steam plant where they also burned peat.

A Memorable Encounter

Another big trip we took, before my retirement, was a European tour. We started in the British Isles and then moved on down through Western Europe. We took an extra week off from the tour in the south of France. After the week we joined up with the next tour and continued on our way through the rest of the countries.

During our visit in the south of France we stopped at Villefranche, which I had visited on the Gridley during the war.

A middle aged woman came to speak with us and listened while I told my story of meeting Claire while in the service just towards the end of the European war.

She asked me if I remember a little knock-kneed girl following her older sister.

I said yes, only to find out that the woman I was speaking with was in fact Claire’s younger sister!

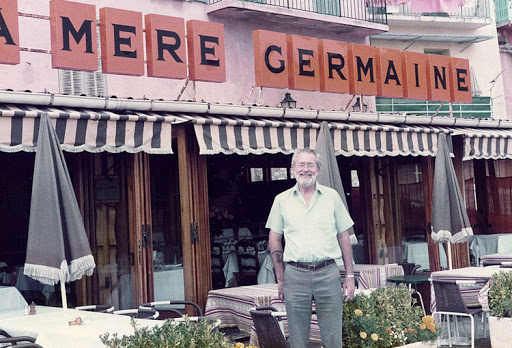

Bob during visit to France in front of La Mere Germaine restaurant

Bob during visit to France in front of La Mere Germaine restaurant

She told us about a July 1959 article in the Reader’s Digest about the restaurant, called “La Mere Germaine” – Madame Remy had owned and operated it until the younger daughter took over.

I retired from PG&E in 1983 after a 37-year career.

The Move to Sonora

Since retirement, we have taken many other trips. We have been to Mexico twice, Hawaii many times (including one time for three months), and two Mississippi cruises on the old Delta Queen.

I moved up to Sonora in 1988 and began building Betty’s and my new home. It was completed in September of 1990. Betty continued commuting to the Bay Area until 1993, due to her work commitments.

After the house was built and I had spare time, I worked as a Hospice volunteer for about 10 years. It was a very rewarding experience. They were glad to have my services because there were very few male volunteers.

Bob on left with shipmates, 2011 Honor Flight to Washington, D.C.

Bob on left with shipmates, 2011 Honor Flight to Washington, D.C.

On May 20, 2011, I flew back to Washington, D.C. on one of the “Honor Flights.” I met up with some other WWII vets from Northern California who were also there.

Reflections

I wanted to serve in the military because America had been attacked.

I was very grateful for the opportunities to fight the enemy and to learn new skills, which were useful even after the war was over. That helped me land the job at PG&E, which gave Betty and me a stable life. The VA benefits also helped me obtain a loan for our first home in San Mateo.

I am not so sure that some of the wars we have been engaged in more recently should have required our participation. They seem to me to be more like civil wars in which we maybe didn’t need to be involved.

I have been to one reunion. When a new “Gridley” destroyer was built, all of us who had served on the original Gridley were invited for the commissioning ceremony. Betty and I went to Miami for that celebration. Only five of us who had served on the original Gridley went. That was on Feb. 10, 2007.

I am a member of the American Legion because my next-door neighbor invited me to attend a meeting. Because of the Honor Flight I was enrolled in the American Veterans Association.

Bob and Betty

Bob and Betty

I would say that serving in the military was good for me, because it matured me. It also gave me experience with electricity which helped me to be hired by PG&E. I knew I could handle that job since I would be dealing with a lot lower frequency than I did during my Navy service!

Medals Awarded to Bob Allured

The American Theatre Medal

Victory Medal WWII

Asiatic Pacific Medal

The World War II Medal

Good Conduct Medal

Philippine Liberation

Bob Allured, Nov. 2013