1st Lt. Pilot-Bombardier, 487th Bombardment Group

as told to Bill and Celeste Boyd

Denny Thompson

I gazed down from the aircraft as we crossed the English Channel and saw hundreds of ships heading for the beaches of France. It was June 6, 1944 and I knew that the troops were hitting the beaches on D-Day as we flew toward Lisieux, France to drop our load of bombs on the German headquarters. I was 21 years old, on my sixth mission flying as a 1st Lt. Pilot-Bombardier in a B-24 Liberator for the 487th Bombardment Group of the Eighth Air Force.

Before I finished my 30th mission six months later, I would be wounded twice and earn two Distinguished Flying Crosses, four Air Medals, four Bronze Stars, the French Freedom Medal, and two Purple Hearts.

Early Days

I was born in Fargo, North Dakota in July 1922 and later moved with my parents, three brothers and one sister to Staples, Minnesota. My dad was a motorcycle policeman in Fargo and later became a “cinder dick” – someone who tried to keep the hobos from riding the rails during the Depression Era – for the Northern Pacific Railway. He had many interesting stories about his experiences policing the railroad. My oldest brother, Vern, and I both worked for the railroad when we graduated from high school.

I got the flying bug during the Depression when the barnstormers came to town and the physician father of a friend paid for an airplane ride for the two of us. It cost $1, was a thrill like no other, and I knew then that I wanted to learn to fly.

Family Service

When World War II started, my two older brothers joined the service. Leroy was a staff sergeant in the South Pacific. He spent three and a half years in New Guinea and earned two Purple Hearts. Vernon, the brother just older than me, was a first lieutenant in the Army Signal Corps in North Africa, and saw action at the Anzio Beachhead. He got hit in the back with shrapnel and earned one Purple Heart. After I joined we were called the “Fighting Thompson Brothers” back home in Minnesota. My youngest brother, Ronald, joined the service late in the war and never saw combat.

Training

I joined the Aviation Cadets in 1943 to prepare for service in World War II. After graduation, I joined the Army Air Corps. My early training was in Brady, Texas in PT-17 biplanes which had the cockpit up high and weren’t very stable. I was coming in just fine on my first solo landing until I ground-looped and touched the grass with a wingtip. [A ground loop occurs when an aircraft is moving on the ground, and pilot error or aerodynamic forces cause one wing to rise and the other wingtip to touch the ground.] The instructor, who like all the other instructors was a civilian, made me sit there for two hours watching the other pilots land.

Later training took place in Salt Lake City, Tucson, and Alamogordo, New Mexico. At first we were flying old B-24s and then a whole cadre of Women’s Air Force (WAF) pilots flew in with the brand new B-24’s. We used to find handwritten notes to the crew tucked into small places inside the planes from gals that worked in the factories building these planes.

As the new planes arrived in Alamogordo we’d do a “shake down” test flight. One very dark night as we were returning back to base from one of these flights, a fuse failed in our plane and all the fuel began pumping into the number two engine tank. Once it was full, the fuel began spewing out and even though we could see it happening we couldn’t stop it. Three miles from the base runway we ran out of fuel and crash-landed. When I jumped out it was so dark I couldn’t even see the ground. Sure enough when we checked the other fuel tanks, they were all empty. No one was hurt but the plane was damaged beyond repair.

In March and early April of 1944, my crew flew our B-24 from Alamogordo by way of Trinidad, Brazil, across to Africa, and then up to England. It’s amazing that less than 17 months from being a clerk on the railroad, I was flying across the English Channel with 10 guys in a 70,000-pound airplane. Since we were a new outfit, we flew into a brand-new base at Lavenham, about 60 miles north of London, where we trained for a month until we flew our first mission on May 6 or 7. We were under the command of Lt. Col. Bernie Lay, Jr. After the war, he co-wrote the book “Twelve O’clock High,” which was made into a film starring Gregory Peck.

Denny and crew, Alamogordo, New Mexico

Bombing Runs

That first mission was to Liege, Belgium where we bombed a power plant. On virtually every mission we were hit by flak put up by the Germans and their fighter planes that met us as we crossed the channel and stayed with us for the whole mission. Since I flew late in the war, we had American fighter planes, P-51 Mustangs and P-47 Thunderbolts, that escorted us to the bomb site and provided protection from the German fighters. The boys who flew in 1942 – ’43 had a lot more action from the German planes because they didn’t have the fighter escort protection we had. The P-47s didn’t have the range to take the bombers clear to Germany, and the Allies didn’t have the P-51s until the spring of 1944.

We named our plane “Problem Child” because so many things went wrong with it when it first arrived in Alamogordo. Almost every plane had a picture and a nickname painted on the sides. I painted the design for “Problem Child” as well as a pair of dice on “Box Car” and a “Dragon Lady” on another one. I was known as Lt. Thompson, the “nose artist.” After every mission we’d carefully paint another bomb on the plane, and I would put one on my leather jacket as well.

Despite the early problems we were often in the lead group as we took off on a bombing run. We would depart from Lavenham and circle over the area for several hours while the rest of the bomb group took off and got into their place in the formation. For the other planes to tell where we were to assemble, we had a special paint job and would shoot flares off above the fog at 16,000 to18, 000 feet. Each mission involved three squadrons totaling 39 planes with nine or ten crew members each, so approximately 390 men were involved. On some missions we put up 2,000 bombers, which is hard to imagine at this point, 67 years later.

Once everybody was gathered in formation, we’d cross the channel and, being heavily loaded with bombs, gradually gained altitude to about 25,000 feet. I have a scar between my eyes where the oxygen mask froze to my face because it gets mighty cold at that high altitude, and to save weight the planes were not insulated. That’s where we’d meet the German fighters, both Messerschmitt ME-109’s and Focke-Wulf 190s, which would be everywhere you looked in the sky above France and Germany. The ME-109 was small and light, but a tough little airplane and very fast and maneuverable.

Our missions were anywhere from five to 11 hours long. We carried a 6,000-pound bomb load except for the lead plane, which carried 3,000 pounds and had a “Tokyo” tank that carried extra gas because it had to fly in circles for two to three hours getting everyone into formation. Our longer missions were to oil refineries, such as in Dresden; on one such mission we hit a German Tiger tank factory, and for that I received a Distinguished Flying Cross. I can still see that factory in my mind as well as several other sites we bombed. We always flew in the daytime but the Brits flew at night. They didn’t fly in formation like we did.

Casualties

We had plenty of energy and enthusiasm for the first 10 missions or so, but after losing a number of planes and crew members, our enthusiasm dwindled until we just wanted to get through our required 30 missions and go home. Replacement crews would come in and we hardly wanted to get acquainted with them because the casualties were so high. Every plane carried 10 or 11 crew members so every time one went down the casualties mounted up fast.

I saw dozens of airplanes go down, mostly from the enormous amount of antiaircraft fire that the Germans put up, but also from planes running into each other now and then. We were raising cain on the German oilfields, so they were short on fuel, airplanes, and pilots by this time. It was cheaper for the Germans to put young soldiers on the ground with the 88mm anti-aircraft guns than to send up their fighters. The 88mm guns could fire straight up, so they were very efficient. There were so many of them sticking up it was like looking at a porcupine. We couldn’t bomb a gun position because it wasn’t worth it…you had to bomb a factory or a railroad yard, and we did. We’d take out a whole rail yard, roundhouses and all, and huge factories because we had so many bombers flying that somebody would hit the target.

After 11 missions we exchanged our B-24s for B-17s, whose backbone was a walkway going all the way back through the middle of the plane. This limited the number and kind of bombs we could carry so we loaded bombs from three-pound incendiaries in 500-pound bundles, 100 pounders, 250s, 500s and 1000-pounders, which were the largest we could carry in our bomb racks. The British planes, however, were more like a fish with the backbone in the top so they could carry the monster bombs, some of them 16,000 pounds. They tumbled end over end because they were flat at both ends, but they did enormous damage. Once we saw a canal they had bombed and it was dry for 200 miles and all the surrounding land was flooded. All the barges were sitting this way and that way in the dry canal.

When we were within a few miles of the target, the pilot tried to keep the plane level and at the required altitude, but the bombardier actually flew the plane and kept it in line for the target. Initially we used the Sperry bombsight, which was not very accurate. Later we got the top secret, much more accurate Norden Bombsight. I practiced constantly on it until I got proficient, and I also studied a big book full of statistics about all the different bombs. As a result, I was the bombardier in the lead plane on many of our missions.

Wounded

During my 27th mission we bombed a truck factory in Cologne; right on the Rhine River that prior to the war had belonged to General Motors. The flak was everywhere and our plane was hit a number of times. Suddenly it felt as if someone had whacked me hard on the cheek. When I removed my big silk gloves and put my hand up to my face, I was bleeding badly. It didn’t hurt that much, but I got blood all over the instruments and switches, and on the guys behind me. We landed safely back at Lavenham, and I was put into the Purple Heart ward, where a number of men had been admitted just after the Battle of the Bulge. It took me about 10 days to heal, and then I was back in the rotation.

My most harrowing mission was the 30th and last in November, 1944, when I was wounded in the arm by antiaircraft flak. Our plane’s fuselage had three or four huge holes in it, and one shell had come through the center of the plane right behind the cockpit but didn’t explode and went up through the top. On the way back to base, we threw out all the machine guns and took the fire axe to the ball turret beneath the plane to lower our weight. When we landed, two of the four engines were out, the hydraulics weren’t working, we had a flat tire, and we counted over 200 holes just in the upright stabilizer.

On approach we shot off a red flare to indicate wounded aboard so the ambulance and the squadron doctor met the plane. The doc said, “Not you again, Thompson,” and gave me a bottle of whiskey for finishing my 30th mission. We had just been issued beautiful brand-new heated flying suits, so when we arrived at the hospital, I wouldn’t let them cut it off to get to my wounded arm. I spent about two weeks in the hospital that time after they removed about 10 pieces of shrapnel. One piece was left in my arm and is still there.

End of the War

When I was almost recovered the Commanding Officer gave me a chance to be immediately promoted and stay on as a Captain instead of being sent home. I turned it down because I didn’t want to fly any more missions. After my release I was sent to Prestwick, Scotland, for the trip home and in the middle of a crap game with about a dozen guys, someone came in and announced that anyone with two Purple Hearts got to fly home on an Air Transport back to the states. I grabbed my money and my bag and in a couple of hours I was in a C-54 on my way home. It wasn’t very comfortable as we sat along the edges of the plane, but it was sure better and a whole lot quicker than coming by ship.

We buzzed the Statue of Liberty and landed in Washington, D.C., where we were met by a brass band. A couple of dozen “hero fighter pilots” were on that flight, some wounded like me (I had my arm in a cast) and we were treated like royalty. I stayed several days and then was put on a train with sleepers and a diner to travel back to Minnesota. I stayed home for a couple of weeks and then was sent to California to a rest camp. After that I spent a little time in Texas as a flight instructor, but before too long, the war was over.

When I got back home to Staples, I began trapping mink and fox which I’d done very successfully before the war. Since no one had been around to trap for several years and there were plenty of animals, I ended up catching about 120 mink that winter. My story was in the Minneapolis papers and people kept calling me wanting to be my partner, because I was getting $30 for a female mink and $40 for a male. The next year the trapping wasn’t as good, and so I went back to work on the railroad for $160 a month.

Alaska

I decided I wanted to get back into the Air Force, as a lot of ex-GIs did, since I had been getting $400 a month with flying pay, had nice clothes and lots of benefits. When I went to apply, so many guys were trying to reenlist that they couldn’t take everyone and I was put on a waiting list as a second lieutenant. They said it would be six months so in the meantime I decided to go to Seward, Alaska where dozens of my friends from the same small town of Staples, Minnesota, had gone. I drove a Jeep and a trailer there in 1947 and shortly thereafter I bought an airplane and never came back to the lower 48 to reenlist.

I did join the Air Force reserve in Anchorage, but since I lived for the first 16 years in Seward, I never got called up. I bought two fishing boats, started an air service, and owned quite a few of the buildings in Seward. Then I built a couple of hunting lodges, the first near McKinley Park called Susitna Lodge, and the second one on the southwestern Alaskan Peninsula called the Newhalen Lodge.

I was a guide and outfitter for almost 60 years and took hundreds of Germans on big game hunts. Although I never took a German fighter pilot, I did guide five generals and the chief surgeon of the German army. One of my customers was Wernher von Braun, who shot a bear, a moose, and a caribou on this hunt. He was one of the leading figures in the development of German rocket technology in WWII. After the war, he and some of his team were taken to the U.S. and assimilated into NASA. He was credited with developing the Saturn V booster rocket that helped land the first men on the moon in July 1969. I never brought up the subject of the war with my German customers, as they were my clients and it just didn’t seem wise.

In the ’70s I guided Fritz Karl Flick, whose family owned Mercedes-Benz and who was one of the richest men in the world at that time. Flick scheduled a spring bear hunt in Alaska because he was pursuing the Weatherby Trophy, awarded to the person who, in a 12-month period, killed one of each species of big game on the planet. Unbeknownst to Flick, I had bombed the hell out of his family’s factories.

Flick shot a bear his first day out and insisted I make room for him on my last flight from camp back to Anchorage. He was eager to fly his private plane back to Germany to go boar hunting. My Super Cub was already overloaded but I managed to stuff the industrialist in the back seat. It was late in the afternoon and the spring sun had caused the surface of the ice covering the lake to turn to a glue-like slush. I cranked the Cub’s engine up to full RPMs and raced across the lake attempting to take off but the skis stuck to the surface of the rotten ice and we couldn’t get airborne.

I bounced the plane a few times attempting to break free. About the third bounce the overloaded plane suddenly broke through the ice, killing the engine. The plane didn’t sink immediately because the wings were hung up on unbroken ice. Ice water flooded into the cockpit as I scrambled out of the plane to the safety of the wing. Flick, accustomed to being waited on hand and foot, remained seated in the back of the sinking plane. I took one look at the dormant German and said, “Karl, your life is not worth a dime more than mine right now, so you better get your own ass out of this airplane.”

I also took the top sharpshooter from the Japanese Army on a hunt for polar bear and caribou. Over the course of those 50-plus years, I put in 25,000 hours on small airplanes, mostly Cessnas and Piper Cubs in Alaska.

Denny and Jeannie, Central African Republic

Africa

I also guided in Africa. There, my partner, Carroll Shelby, race driver and car designer whose projects included the Cobra and Mustang GTs, and I had a base in the Central African Republic, a landlocked nation located dead center in the middle of Africa. From there I flew Piper Senecas, which could hold six people on hunts for African big game. We built a huge building with about 20 Land Rovers and trucks in it, and had about 13 professional hunters working for us. The last man I guided in Africa was an Indonesian prince who later invited me on a tiger hunt. I took him up on the offer, but never even saw a tiger.

Earthquake

At one point I had a list of every mission I had flown but in 1964 all my records and photos were destroyed by a magnitude 9.2 earthquake in Alaska. It occurred on March 27 in the Prince William Sound and the Gulf of Alaska and caused landslides, ground fissures, and many local tsunamis. One tidal wave washed over the Seward Airfield where I had stored all my stuff and two airplanes in hangars. I lost all my memorabilia except my leather flying jacket and uniform.

Fortunately both airplanes were out on polar bear hunts that day or I would have lost them, too.

Reunions

The 487th included about 6,000 men, and about 500 of them were flight crew members. The remainder were “ground stompers,” our name for ground crew members. I’ve been to every reunion of the 487th, the last one in Fort Myers, Florida, and this year in October it was in Savannah, Georgia, where the big 8th Air Force Museum was built.

Now, however, there are fewer than a dozen guys left from my group out of about 2,500 men, and only the wives and children of the other airmen attend. Starting last year we combined our reunion with the 486th, our sister group who were stationed about six miles away from us in England, because the numbers were getting so low.

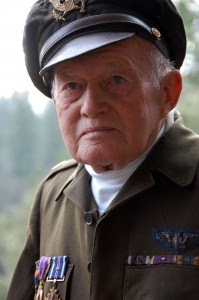

Age 89, in WWII jacket

Marriage and Family

I met my first wife, Jean, when I was in high school in Staples and we married when I returned after the war. We later divorced and I married Marge, who lived in Alaska with me.

My third wife, Jeannie, was a lot younger than I and had worked as our babysitter. We fell in love and were married almost 30 years when she died of cancer four years ago. We moved to Sonora in 1986, because I had guided and become friends with a number of people from this area. Also I had gone into partnership with one of those friends to build a mini-storage up at Camp Sunshine. That didn’t work out, and eventually I sold the property. However, I did keep a twin turbine plane at Columbia Airport and could fly from here to Anchorage in one day.

My family now consists of three sons and two daughters and their children. My two oldest sons, Denny Jr. and Lee, own airplanes in Alaska, and my other son, Mark, is a computer engineer for Hewlett Packard. My daughter, Jennifer, is a registered nurse in Alaska, and my other daughter, Janice, lives here in Sonora. I have nine grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

For years I used my two fishing boats to catch and deliver salmon to the “Dangerous Catch” boats anchored out in the ocean west of Alaska. Three years ago I decided I was too damn old to be fishing anymore and sold both of my boats. But this year I bought another one, a welded aluminum one like all the others – I guess it’s in my blood. I still own a home and once again a 37-foot commercial fishing boat in King Salmon, Alaska. When I went to Alaska in July 2011, I took my granddaughter Michaela’s boyfriend, a mechanic, with me to work on the boat and my 14-year-old grandson worked on my fishing boat there this past summer.

Mr. Thompson at home, January 2012

Reflections

My wife, Jeannie, and I returned to the American cemetery in Normandy in 1995 for the 50th D-Day anniversary and again for the 55th, 60th and by myself for the 65th. God willing, I’ll be there for the 70th, too. During the 55th commemoration ceremony at the American Cemetery where I had presented a wreath, I met a French civilian who was a child in Lisieux in 1944 and he clearly remembered the night of the bombing. The Allies had dropped leaflets in the night prior to the bomb run telling the people in the area to get out of town before the bombing began. He said his whole family went up the hills into the forest and could see everything that was happening to the town.

Recently I participated in an Honor Flight to Washington D.C. sponsored by the nonprofit Honor Flight Network which flies veterans from all over the country free of charge to the Capitol to see the memorials that have been erected in their honor. All of the vets who went were treated like royalty. When we returned to San Francisco we were greeted by several hundred people who were waving flags and cheering. It was a good feeling.

I can still wear the same uniform that I wore when I was discharged on Nov. 5, 1945. All of my children have been to see the area where I was stationed in England and the Normandy sites, and two years ago we took my 12-year-old twin grandchildren there.

My time in the Air Force provided me with leadership and flying skills, which allowed me to make a good living for the rest of my working days. I made some good friends and enjoyed meeting with the ones who survived the war at our reunions. I remain active in WWII memorials and traveled to Washington, D.C. in the fall of 2011 as part of a cadre to honor the fallen men from that time. I am a member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and have walked in many parades here in Sonora.

I am proud to share the stories of my service with my family and friends so they can learn to appreciate the sacrifices made by so many to keep our country free. Looking at photos and memorabilia is good, but by actually traveling to the historic places, the stories mean so much more to them now.